The #1 topic of discussion in Leipzig art circles this week has been the announcement by city officials of approval for a new Holocaust museum, to be built in the former Soviet pavilion on the grounds of the old Leipzig trade fair. Developers had previously hoped to build a multiplex cinema in the pavilion, with its church-like steeple topped by a massive red star.

Renowned German architect Meinhard von Gerkan has been selected to design the project. Von Gerkan was responsible for Berlin’s new central rail station and is currently involved in planning a new Chinese city outside Shanghai, as well as designing several soccer stadiums in South Africa for the 2010 World Cup.

Planners feel housing the museum in the former Soviet pavilion will allow the institution to expand discussion beyond the Holocaust, to anti-Semitic oppression during the Soviet era, a period in which many surviving Jewish leaders were sent to labour camps or into exile. In an interview in Die Zeit, historian Frank Nesemann of Leipzig’s Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture said he believed broadening the dialogue to include the state-sanctioned anti-Semitism of the GDR and Soviet Union will contribute to our understanding of the rise of genocidal regimes.

There’s an English-language story in Deutsche Welle, but it focuses primarily on the architect. Here’s a link to a more comprehensive story in the European Jewish Press.

Central Europe's leading English-language arts blog. MuseumZeitraum Leipzig, celebrating the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann (1841-1898), opening Autumn 2016. Supported by the Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Monday, November 27, 2006

My Weimar weekend

Johann Dieter Wassmann, GOETHEHAUS, WEIMAR, 1894.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, GOETHEHAUS, WEIMAR, 1894. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 736004.

The weekend saw a trip to Weimar, where I celebrated an American Thanksgiving (two days late) with senior staff from The Wassmann Foundation, including director Jeff Wassmann, at the city’s celebrated Hotel Elephant. Despite its role as the epicenter of German Enlightment, Weimar remains as intimate and cozy as it must have been then, all the more so in autumn.

The highlight for me, however, was a short stroll over to the grounds of the first Bauhaus School, originally designed as the School of Arts and Crafts by Henry van de Velde in 1907. A nephew of Johann Dieter Wassmann was one of the carpenters responsible for the iconic spiral staircase in what is now the College of Architecture, Building and Construction. This central building, recently renovated to its early glory, always guarantees me goose bumps, as a life-long student of modernism.

No less inspiring was my pilgrimage to Goethe’s home, now a museum, pictured here in a photograph by Johann in 1894. Unfortunately, the Nietzsche Archives was closed when we popped by, but the stunning Art Nouveau building was worth a peak through the gate all the same.

The good news is that I can report we appear one step closer to completing a repatriation agreement with the Wassmann Foundation, bringing the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann long-last home to Leipzig. Stay tuned…

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Nietzsche 306P

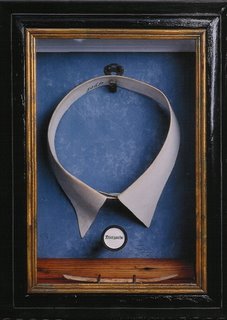

Johann Dieter Wassmann, NIETZSCHE 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, NIETZSCHE 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm. The lesser-known companion piece to yesterday's post, IN THE STAR CHAMBER, is Johann's provocative work, NIETZSCHE 306P.

In 1889, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown, often attributed to his contraction of syphilis, resulting in his admission to various clinics before he was moved to Naumburg, where his mother looked after him until her death in 1897. At that point his sister Elisabeth shifted him to Weimar, where she continued his care, as well as promoting his legacy and allowing the occasional audience with guests until his death in 1900.

It was in Weimar that Johann briefly visited Nietzsche, but finding only a shell of a man he returned home to produce this work, depicting simply and eloquently the empty collar of the man, an organ stop with the name 'Nietzsche' printed on it, and an opium-stained bone apothecary spoon. The objects are placed against a dappled blue wall, reflecting Nietzsche's penchant for blue-lensed spectacles.

Our thoughts go out today to the family of Nietzsche's most recent biographer, Curtis Cate, who we understand passed away earlier this week in Paris at the age of 82. The New York Times is preparing an obituary for publication in the next few days. In the meantime, here's a link to the Times review of Curtis's biography, FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE (Overlook Press), from August of last year.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

In the Star Chamber

Saturday, November 18, 2006

16969

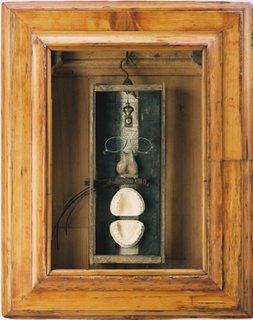

Johann Dieter Wassmann, 16969, 1896. 440 x 310 x 150 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, 16969, 1896. 440 x 310 x 150 mm. By request, I'm posting an enlarged view of the central work in the installation "Planck's Constant", which I showed you Thursday. The piece is currently in the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C., pending finalisation of a repatriation agreement that will see the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann return home to Leipzig for our July 2008 opening (preferably with time to spare).

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Planck's Constant

Here's a look back at "Planck's Constant", last seen in 1998 at The Wassmann Foundation’s Centennial Exhibition in Washington, D.C. The installation explores the intellectual convergence that occurred through Johann Dieter Wassmann's friendship with the physicist Max Planck. The installation will be restaged at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig’s inaugural exhibition in 2008.

Here's a look back at "Planck's Constant", last seen in 1998 at The Wassmann Foundation’s Centennial Exhibition in Washington, D.C. The installation explores the intellectual convergence that occurred through Johann Dieter Wassmann's friendship with the physicist Max Planck. The installation will be restaged at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig’s inaugural exhibition in 2008.

Monday, November 13, 2006

MuseumZeitraum construction update

I've realised I'm long overdue for an update on MuseumZeitraum's construction progress. Here's a look at the sub-basement, which will one-day house the museum's archives. Finance and final architectural plans are pending, but we're still on track for our summer 2008 opening (fingers crossed). For an exterior view, have a look at my August 24 post.

I've realised I'm long overdue for an update on MuseumZeitraum's construction progress. Here's a look at the sub-basement, which will one-day house the museum's archives. Finance and final architectural plans are pending, but we're still on track for our summer 2008 opening (fingers crossed). For an exterior view, have a look at my August 24 post.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Mut zur Lücke

Johann Dieter Wassmann, PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. 660 x 530 x 130 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. 660 x 530 x 130 mm.The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (Overlook Press) has prompted several commentators to disparage the Guild of Funerary Violinists as something of a 'pre-modern' relic. This points up a significant misunderstanding of the role of the funerary violinist in the development of the modern era, a misunderstanding that warrants further discussion.

Pope Gregory XVI’s instigation of the Great Funerary Purges of the 1830s and 1840s was a deliberate, and it must be said effective, strike at the spartan musical form advocated by funerary violinists, a form that we now appreciate revealed the buds of early modern intellectual independence. As Kriwaczek rightly points out (see Wednesday's post), “…the genre of Funerary Violin evolved in its own distinct manner, following a path of rooted modality and direct expression, and eschewing all displays of virtuosity… in order to explore simply and honestly our relationship with our own and others’ mortality.” This reductivist urge, which I might also add was largely devoid of narrative, was a radical departure by any measure, but like the electric car in our current age, powerful forces made certain it was not to be, at least not yet. When it did find a foothold in the late 19th century, success was the domain of others.

In the visual arts, a similar reductivism came to inform the boxed works of Johann Dieter Wassmann in the 1890s. Not surprisingly, Johann’s elder brother, Hugo Wassmann, was himself a funerary violinist, as I have mentioned. In her essay, "A Carpenter's Tale," Maime Stombock points out that it was Johann’s sudden and humiliating recognition in 1889 of the depth of his own bourgeois values that long last allowed the fog to lift:

"The final period of work that grew out of these revelations can only be described as early modern. Johann's competence as a carpenter, along with his total command by this point of the medium of the wooden box, allowed him to plunge headlong into works unlike anything he had considered prior. The most striking feature of these pieces is their simplicity of line, plane and form. This new sensibility he referred to by the German expression die Mut zur Lücke -- the courage to leave things out. Several works even verge on abstraction, most notably his politically charged pair KAISER WILHEM II, 1894 and PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. The enigma of these works, an enigma which creates puzzlement even today, rests in the subtlety of their comment, rather than in the compelling presence of a narrative, as was often the case in earlier works."

READ MORE

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

The Art of Funerary Violin

A post-election day reading from Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (New York: Overlook Press, 2006):

A post-election day reading from Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (New York: Overlook Press, 2006): “(T)he genre of Funerary Violin evolved in its own distinct manner, following a path of rooted modality and direct expression, and eschewing all displays of virtuosity, in terms of both performance and compositional artistry, in order to explore simply and honestly our relationship with our own and others’ mortality, in all its many and varied historical and cultural aspects. Had it survived until today, who knows how it would have reflected our current disowning of death; however, it is certain that it would have proved more profound and deeply cathartic than the contemporary tendency towards recorded music played on a ghetto blaster. But then maybe a spiritless age deserves a spiritless death. It is not for me to judge.”

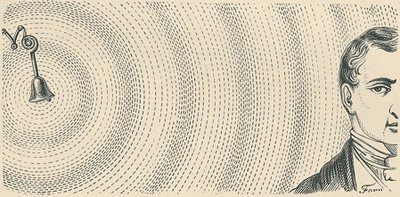

Engraving by J. Forn from the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Music of the Spheres

Johann Dieter Wassmann, HARMONISCH 1895. 145 x 145 x 70 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, HARMONISCH 1895. 145 x 145 x 70 mm.Last week I focused on the composer Hugo Wassmann's involvement with the Guild of Funerary Violinists and the Mizler Society, a theme I don't want to leave just yet, so this week I thought I'd open by looking at the impact of music on Johann Dieter Wassmann's boxed works. Maime Stombock makes the point in her essay, "A Carpenter's Tale," that it was Johann’s friendship with the physicist Max Planck, and their mutual interest in the epistemology of music, that in many ways directed his thinking:

"The late night dialogues Johann records between himself and Planck more often than not centered around music. But then, he was a Leipziger: Wagner, Mendelssohn, Strauss, Liszt, Schumann, Brahms, Grieg, Mahler, they all spent crucial years in the city (as well as in Weimar) during the course of Johann’s life, allowing him to come in contact with each, as well as to see all but Wagner and Schumann either conduct or perform. It would be impossible to overstate the importance of music in his work, despite there being only a handful of direct musical references in his boxes.

"For Johann, music and only music could create such an idealization of space as to transcend time, while still existing within it as an undivided whole. Music is at once truth and form, knowledge and sensation. Music defies absolute space and time by not only transcending the boundaries, but by suggesting the very boundlessness of the universe itself.

"Another to have passed through Leipzig—in this case on his way to Vienna—was Sigmund Freud. In Freud, Johann found his journey had come full circle. Where Johann had begun by challenging his students to question the veracity of truth through his enigmatic displays on human physiology, he ended by proffering that truth is neither supreme nor absolute; our universe may be governed by laws, he suggests, but truth resides just outside our reach, amidst the deepest dark corners of a world we have only just begun to unravel: that of the human mind."

READ MORE

Friday, November 03, 2006

Saxony-Anhalt 1897

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Hugo Wassmann & The Mizler Society

The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN has opened a pandora’s box of questions surrounding Hugo Wassmann’s involvement in the Guild of Funerary Violinists. No less puzzling, however, were Hugo’s ties to the Mizler Society. This late-Baroque musical society was founded by Loren Christoph Mizler von Kolof for the programmatic study of music’s innate relationship to science. Mizler, who attended the University of Leipzig and was a former student of Bach’s, devoted his master's thesis, “Quod musica ars sit pars eruditionis philosophicae,” to the development of a scientific approach to music grounded in mathematics and philosophy. Early members of the society included Bach, Handel and Telemann. Gatherings posed such troubling questions as why parallel fifths were undesirable.

The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN has opened a pandora’s box of questions surrounding Hugo Wassmann’s involvement in the Guild of Funerary Violinists. No less puzzling, however, were Hugo’s ties to the Mizler Society. This late-Baroque musical society was founded by Loren Christoph Mizler von Kolof for the programmatic study of music’s innate relationship to science. Mizler, who attended the University of Leipzig and was a former student of Bach’s, devoted his master's thesis, “Quod musica ars sit pars eruditionis philosophicae,” to the development of a scientific approach to music grounded in mathematics and philosophy. Early members of the society included Bach, Handel and Telemann. Gatherings posed such troubling questions as why parallel fifths were undesirable.Hugo Wassmann (Johann Dieter Wassmann's next elder brother, pictured dimly here in 1869) was introduced to the then-struggling Mizler Society while studying philosophy at the University of Leipzig. For reasons that are not well understood, Hugo remained a devotee to this antiquated, and decidedly anti-modern, society right up until his death in Weimar in 1915, at the age of 76.

A charming website examining the Mizler Society was recently launched by violinist John Rodgers, so turn up your speakers, click through and enjoy.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Hugo Wassmann & the Guild of Funerary Violinists

Several correspondents across the Atlantic have, in recent days, raised queries over Hugo Wassmann’s falling out with the Guild of Funerary Violinists in 1901 (last Thursday's post). CRWM, writing on the blog AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS (link below) asks, “Did you not find it interesting that [Rohan Kriwaczek's] AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY failed to mention the irony that brother of one of the greatest proto-modernists was one of the last links to this most pre-modern of traditions?” Indeed, this fraternal relationship is a curious one, but I also find it telling that it was only after Johann’s death in 1898 that Hugo reconsidered his affiliation with the Guild.

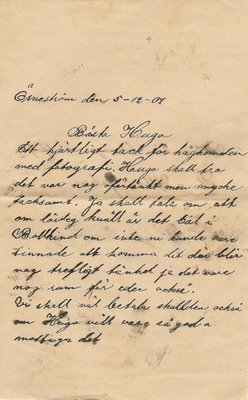

Several correspondents across the Atlantic have, in recent days, raised queries over Hugo Wassmann’s falling out with the Guild of Funerary Violinists in 1901 (last Thursday's post). CRWM, writing on the blog AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS (link below) asks, “Did you not find it interesting that [Rohan Kriwaczek's] AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY failed to mention the irony that brother of one of the greatest proto-modernists was one of the last links to this most pre-modern of traditions?” Indeed, this fraternal relationship is a curious one, but I also find it telling that it was only after Johann’s death in 1898 that Hugo reconsidered his affiliation with the Guild. A letter from the noted Swedish music publishers Elin and Ulla Johnson, dated 5 December 1901 and addressed to Hugo, sheds some light on Hugo’s state of mind in coming to what must have been a wrenching decision (above). The letter is currently in the archives of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Although written in an old Swedish dialect, I will translate as best I can.

The letter opens thanking Hugo for a photograph (fotographi) he has recently sent them. They then go on to reassure Hugo he has made the right decision in leaving the Guild (def Gál), heartening him with the conviction that the saxophone will one day be the centrepiece of both orchestral and funerary composition, although not necessarily among Lutherans. The letter closes with this encouragement: “The burden is on your shoulders Hugo but God will provide.” It is signed on the reverse, “Elin & Ulla Johnson,” with the added remark, “…send Helge and Eva our love.” Helge and Eva were Hugo’s two surviving daughters.

I hope this sheds further light on the last remaining years of the Guild.