Johann Dieter Wassmann, Guardian Angel, 1888. 660 x 450 x 60mm. Day seven in the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Guardian Angel, 1888. 660 x 450 x 60mm. Day seven in the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Seven shiny marbles

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Guardian Angel, 1888. 660 x 450 x 60mm. Day seven in the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Guardian Angel, 1888. 660 x 450 x 60mm. Day seven in the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Six moments passing

Friday, December 29, 2006

Five traits to ponder

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Four Medicean Stars

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Three noble virtues

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Two martrys in an elm tree

Monday, December 25, 2006

The Twelve Days of Christmas... a child is born

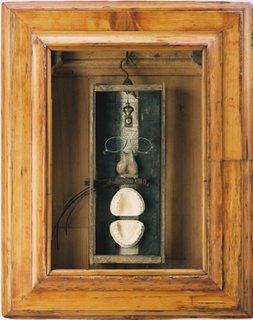

Johann Dieter Wassmann, L'Enfant Moses, 1893. 335 x 250 x 155mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, L'Enfant Moses, 1893. 335 x 250 x 155mm. Throughout Christendom, the Twelve Days of Christmas begins this evening. To celebrate, I will present a gift each day of the lesser-known works of Johann Dieter Wassmann. Here Johann depicts not the baby Jesus, but Moses on the River Nile. From inside a protective jar he peers out at a duck egg, from which the artist would appear to suggest the infant has recently emerged.

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Eppur Si Muove

The Australian film-maker Richard Moore sent along word overnight that a trailer from his upcoming documentary The Foundation can now be seen on YouTube. While the clip focuses on Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann, Richard assures me the final cut of the film will examine more broadly the life and art of Johann Dieter Wassmann, along with the efforts of MuseumZeitraum to repatriate Johann’s works home to his native Leipzig.

The Australian film-maker Richard Moore sent along word overnight that a trailer from his upcoming documentary The Foundation can now be seen on YouTube. While the clip focuses on Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann, Richard assures me the final cut of the film will examine more broadly the life and art of Johann Dieter Wassmann, along with the efforts of MuseumZeitraum to repatriate Johann’s works home to his native Leipzig.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Ruth Bernhard 1905 - 2006

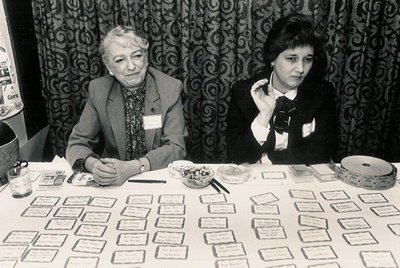

Ruth Bernhard, Chicago, Illinois, 1981. Photograph: Sophie Vogt.

Ruth Bernhard, Chicago, Illinois, 1981. Photograph: Sophie Vogt.Earlier today, I learned of the passing of Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco at the age of 101. When I first met Ruth in 1981, she was already 76 but I had little doubt she had 25 good years left in her. She has proven me correct. With an iron will and unswerving modernist convictions, Ruth was truly one of the greats of 20th century photography. She will be remembered as an inspired teacher and mentor to many, including myself.

Born in Berlin in 1905, Ruth studied at the Academy of Fine Arts before following her father to New York in the 1920s. A decade later, she headed west to Hollywood where she met Edward Weston, who would become her dear friend and soul-mate. Ruth soon reduced the nude to pure essence, creating several of the most iconic images of the female form of the modernist era, most notably In the Box, Horizontal 1962.

I first met Ruth in Chicago when she was touring with Margaretta K. Mitchell’s exhibition Ten Women of Photography. Accompanying her were two other greats of 20th century photography, Lotte Jacobi and Barbara Morgan. All are gone now, but the legacies of their kindness, vision and pioneering spirit will outlast us all.

Here’s a link to Ruth’s obituary in this morning’s Los Angeles Times.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Zaha Hadid's crystal ball

Earlier this morning I had a breakfast meeting with executives at BMW's ultra-modern Zaha Hadid-designed Leipzig car plant as the Zeitraum Challenge spreads its wings in search of support to assure MuseumZeitraum reaches its full potential. While all talks remain confidential, I can say, what a remarkable place to go to work every day. Time to give up curating and start punching the clock. Here's a link with a look into the future of the workplace.

Earlier this morning I had a breakfast meeting with executives at BMW's ultra-modern Zaha Hadid-designed Leipzig car plant as the Zeitraum Challenge spreads its wings in search of support to assure MuseumZeitraum reaches its full potential. While all talks remain confidential, I can say, what a remarkable place to go to work every day. Time to give up curating and start punching the clock. Here's a link with a look into the future of the workplace.

Friday, December 15, 2006

L'Origine du monde

Johann Dieter Wassmann, SCHLOSS, AUGUSTBURG, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 725014.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, SCHLOSS, AUGUSTBURG, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 725014.With the first forecast of snow in the coming days and Miami long forgotten, I thought I'd end the week with this rather suggestive, if brutalist, image -- bearing a clear reference to Courbet's L'ORIGINE DU MONDE, 1866 -- from the archives of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

If art matters

Johann Dieter Wassmann, ZEIT-RAUM, 1896. 470 x 270 x 160mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, ZEIT-RAUM, 1896. 470 x 270 x 160mm.I suspect few of the 40,000 heading home this weekend from Miami Basel chose the window seat for their return travel (excepting, of course, locals, those with private jets and those for whom the window seat was the last remaining in first class). It’s not a ‘window seat’ kind of crowd. Watching the lights of the Brittany coastline twinkle below on my way in to Frankfurt, I pine for the days when it was otherwise. I struggle to imagine Joseph Beuys strutting his stuff daily on South Beach, with his entourage in tow, or Marcel Duchamp screaming “I HAVE a reservation,” at Joe’s Stone Crab, both events I witnessed by artists who shall remain un-named. Art Basel Miami Beach is strictly Warhol territory, as is the art-world at large today.

Were Johann Dieter Wassmann to reincarnate himself in the present, I have little doubt he would be sitting in the window seat, as I am. Looking out through this tiny porthole into the night sky at 37,000 feet, I’m reminded of his work ZEIT-RAUM, the namesake for our museum dedicated to his life’s work. ‘Space-Time’, both as a work and as an institution, is a portal of sorts, a suspended moment that takes us from the mundane of everyday life into a slipstream of possibilities, where art is our chosen mode of transport and hope and dreams remain unbounded, not simply a tool for capital gain.

When I land in Frankfurt, I’ll have a three-hour delay before heading home to Leipzig, time enough to send this post and dash over to the Städelsches Kunstinstitut to spend another treasured moment with Vermeer’s GEOGRAPHER. Another time, another place, but a portal like no other. If art truly matters, this is still the reason why.

Friday, December 08, 2006

Welcome to the machine

Given my life as a curator, rather than collector or critic, my intent in coming to Art Basel Miami Beach had been to engage in the discourse of the event, rather than wallow in celebrity, parties and gross revenues. How silly of me.

Given my life as a curator, rather than collector or critic, my intent in coming to Art Basel Miami Beach had been to engage in the discourse of the event, rather than wallow in celebrity, parties and gross revenues. How silly of me. There is no discourse in Miami. There is only money. While I’m not often prone to admit it, Robert Hughes was right about one thing. As he told The Guardian earlier this year, "The present commercialisation of the art world, at its top end, is a cultural obscenity.” Nothing could better describe these past few days, time spent in such vapid pursuits they're hardly worth reporting. The few programmed events that had promised more, such as the Conversation series, were either cancelled (Jacques Herzog was a no-show) or simply banal (a discussion this morning on what else – collecting).

So if you didn’t make it to Miami, don’t fret. My advice: from now till summer, put aside $10 a day (less if you live in Europe) and head to Kassel for Documenta 12, the last holdout on the art circuit where 'dis-course' doesn't refer to a pudgy-fingered New Yorker pointing to what he wants off the luncheon menu.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Vernissage Art Basel Miami Beach

Pictured: Artist Sally Smart at Jacob Karpio Galeria (Costa Rica)

Pictured: Artist Sally Smart at Jacob Karpio Galeria (Costa Rica)Art Basel Miami Beach is to art appreciation what Pamplona is to animal welfare. They also launch themselves in much the same manner. And the bulls are certainly running this evening here at ABMB’s Vernissage (brought to you in real time via BlackBerry). It would be doing no one justice to offer critique amidst such a well-groomed stampede, nor would it do me much good to continue nursing this metaphor. I will say, however, that the stand-out artist on first look is Sally Smart, an Australian showing at Jacob Karpio. Her ‘Exquisite Pirate’ installation, an expansive work exploring the discourse of women pirates (shown at ABMB on reduced scale) has been the talk of New York since Jerry Saltz’s rave about her in The Village Voice earlier in the year when the work was shown at Postmasters. The installation is currently on view at Jacob’s San Jóse gallery; an all-new work on the theme is set to open at Hunter College’s mid-town gallery next month. We would hope to see her across the pond sometime soon. First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin?

You won’t find Smart listed on ABMB’s web catalogue, as we suspect she was a late ring-in, but here’s a link to her own website:

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Hot, hot, hot

Art Basel Miami Beach doesn’t officially open until Thursday, but the art of commerce has been well under way for several days. Earlier this evening, I stopped by the UBS party on South Beach, where Tyler Green enthusiastically explained to me, “Miami is the new Davos.” Less the protesters, Tyler.

Art Basel Miami Beach doesn’t officially open until Thursday, but the art of commerce has been well under way for several days. Earlier this evening, I stopped by the UBS party on South Beach, where Tyler Green enthusiastically explained to me, “Miami is the new Davos.” Less the protesters, Tyler. Landing in Miami mid-day, the tarmac was already crammed with private jets hunkered down for the week. Curbside, BMW’s fleet of 25 chauffeured 7-series motor cars was busy ushering VIP guests to and fro -- indeed, die dynamischste Limousine der Oberklasse. I might have caught a glimpse of Dennis Hopper gliding away in one, but I can't be certain.

What a difference a year and a mid-term election make. 12 months ago, we ‘old’ Europeans were on the receiving end of profuse apologies for the actions of The Great War-Monger, as Borat hails him. Today, it’s victory to the left and the war seems largely forgotten. Too bad no one told those poor sods still in the trenches, the ones who forgot to go to Yale, that the war is resolved. Might I remind you, it isn't.

Oh yes, if you were hoping to learn something about art in Miami, I haven’t spotted any yet, just commerce. Tomorrow's another day.

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Miami FLA...

Like the lemming that I am, it’s Frankfurt-to-Miami via Dulles later today for the madness of Art Basel Miami Beach. Monday and Tuesday, I’ll be stopping through Washington, D.C., as negotiations continue with The Wassmann Foundation to repatriate the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann home to his native Leipzig. Technology, immigration and sobriety permitting, I’ll do my best to keep you posted through the week.

Friday, December 01, 2006

Freundschaftstempel

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Leipzig Holocaust Museum

The #1 topic of discussion in Leipzig art circles this week has been the announcement by city officials of approval for a new Holocaust museum, to be built in the former Soviet pavilion on the grounds of the old Leipzig trade fair. Developers had previously hoped to build a multiplex cinema in the pavilion, with its church-like steeple topped by a massive red star.

Renowned German architect Meinhard von Gerkan has been selected to design the project. Von Gerkan was responsible for Berlin’s new central rail station and is currently involved in planning a new Chinese city outside Shanghai, as well as designing several soccer stadiums in South Africa for the 2010 World Cup.

Planners feel housing the museum in the former Soviet pavilion will allow the institution to expand discussion beyond the Holocaust, to anti-Semitic oppression during the Soviet era, a period in which many surviving Jewish leaders were sent to labour camps or into exile. In an interview in Die Zeit, historian Frank Nesemann of Leipzig’s Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture said he believed broadening the dialogue to include the state-sanctioned anti-Semitism of the GDR and Soviet Union will contribute to our understanding of the rise of genocidal regimes.

There’s an English-language story in Deutsche Welle, but it focuses primarily on the architect. Here’s a link to a more comprehensive story in the European Jewish Press.

Renowned German architect Meinhard von Gerkan has been selected to design the project. Von Gerkan was responsible for Berlin’s new central rail station and is currently involved in planning a new Chinese city outside Shanghai, as well as designing several soccer stadiums in South Africa for the 2010 World Cup.

Planners feel housing the museum in the former Soviet pavilion will allow the institution to expand discussion beyond the Holocaust, to anti-Semitic oppression during the Soviet era, a period in which many surviving Jewish leaders were sent to labour camps or into exile. In an interview in Die Zeit, historian Frank Nesemann of Leipzig’s Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture said he believed broadening the dialogue to include the state-sanctioned anti-Semitism of the GDR and Soviet Union will contribute to our understanding of the rise of genocidal regimes.

There’s an English-language story in Deutsche Welle, but it focuses primarily on the architect. Here’s a link to a more comprehensive story in the European Jewish Press.

Monday, November 27, 2006

My Weimar weekend

Johann Dieter Wassmann, GOETHEHAUS, WEIMAR, 1894.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, GOETHEHAUS, WEIMAR, 1894. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 736004.

The weekend saw a trip to Weimar, where I celebrated an American Thanksgiving (two days late) with senior staff from The Wassmann Foundation, including director Jeff Wassmann, at the city’s celebrated Hotel Elephant. Despite its role as the epicenter of German Enlightment, Weimar remains as intimate and cozy as it must have been then, all the more so in autumn.

The highlight for me, however, was a short stroll over to the grounds of the first Bauhaus School, originally designed as the School of Arts and Crafts by Henry van de Velde in 1907. A nephew of Johann Dieter Wassmann was one of the carpenters responsible for the iconic spiral staircase in what is now the College of Architecture, Building and Construction. This central building, recently renovated to its early glory, always guarantees me goose bumps, as a life-long student of modernism.

No less inspiring was my pilgrimage to Goethe’s home, now a museum, pictured here in a photograph by Johann in 1894. Unfortunately, the Nietzsche Archives was closed when we popped by, but the stunning Art Nouveau building was worth a peak through the gate all the same.

The good news is that I can report we appear one step closer to completing a repatriation agreement with the Wassmann Foundation, bringing the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann long-last home to Leipzig. Stay tuned…

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Nietzsche 306P

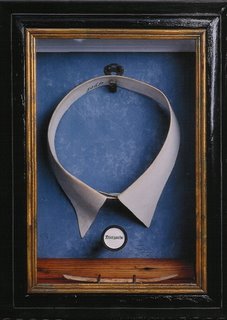

Johann Dieter Wassmann, NIETZSCHE 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, NIETZSCHE 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm. The lesser-known companion piece to yesterday's post, IN THE STAR CHAMBER, is Johann's provocative work, NIETZSCHE 306P.

In 1889, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown, often attributed to his contraction of syphilis, resulting in his admission to various clinics before he was moved to Naumburg, where his mother looked after him until her death in 1897. At that point his sister Elisabeth shifted him to Weimar, where she continued his care, as well as promoting his legacy and allowing the occasional audience with guests until his death in 1900.

It was in Weimar that Johann briefly visited Nietzsche, but finding only a shell of a man he returned home to produce this work, depicting simply and eloquently the empty collar of the man, an organ stop with the name 'Nietzsche' printed on it, and an opium-stained bone apothecary spoon. The objects are placed against a dappled blue wall, reflecting Nietzsche's penchant for blue-lensed spectacles.

Our thoughts go out today to the family of Nietzsche's most recent biographer, Curtis Cate, who we understand passed away earlier this week in Paris at the age of 82. The New York Times is preparing an obituary for publication in the next few days. In the meantime, here's a link to the Times review of Curtis's biography, FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE (Overlook Press), from August of last year.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

In the Star Chamber

Saturday, November 18, 2006

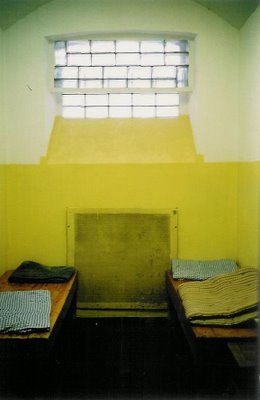

16969

Johann Dieter Wassmann, 16969, 1896. 440 x 310 x 150 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, 16969, 1896. 440 x 310 x 150 mm. By request, I'm posting an enlarged view of the central work in the installation "Planck's Constant", which I showed you Thursday. The piece is currently in the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C., pending finalisation of a repatriation agreement that will see the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann return home to Leipzig for our July 2008 opening (preferably with time to spare).

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Planck's Constant

Here's a look back at "Planck's Constant", last seen in 1998 at The Wassmann Foundation’s Centennial Exhibition in Washington, D.C. The installation explores the intellectual convergence that occurred through Johann Dieter Wassmann's friendship with the physicist Max Planck. The installation will be restaged at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig’s inaugural exhibition in 2008.

Here's a look back at "Planck's Constant", last seen in 1998 at The Wassmann Foundation’s Centennial Exhibition in Washington, D.C. The installation explores the intellectual convergence that occurred through Johann Dieter Wassmann's friendship with the physicist Max Planck. The installation will be restaged at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig’s inaugural exhibition in 2008.

Monday, November 13, 2006

MuseumZeitraum construction update

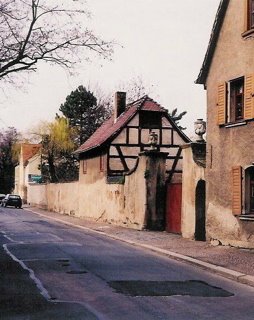

I've realised I'm long overdue for an update on MuseumZeitraum's construction progress. Here's a look at the sub-basement, which will one-day house the museum's archives. Finance and final architectural plans are pending, but we're still on track for our summer 2008 opening (fingers crossed). For an exterior view, have a look at my August 24 post.

I've realised I'm long overdue for an update on MuseumZeitraum's construction progress. Here's a look at the sub-basement, which will one-day house the museum's archives. Finance and final architectural plans are pending, but we're still on track for our summer 2008 opening (fingers crossed). For an exterior view, have a look at my August 24 post.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Mut zur Lücke

Johann Dieter Wassmann, PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. 660 x 530 x 130 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. 660 x 530 x 130 mm.The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (Overlook Press) has prompted several commentators to disparage the Guild of Funerary Violinists as something of a 'pre-modern' relic. This points up a significant misunderstanding of the role of the funerary violinist in the development of the modern era, a misunderstanding that warrants further discussion.

Pope Gregory XVI’s instigation of the Great Funerary Purges of the 1830s and 1840s was a deliberate, and it must be said effective, strike at the spartan musical form advocated by funerary violinists, a form that we now appreciate revealed the buds of early modern intellectual independence. As Kriwaczek rightly points out (see Wednesday's post), “…the genre of Funerary Violin evolved in its own distinct manner, following a path of rooted modality and direct expression, and eschewing all displays of virtuosity… in order to explore simply and honestly our relationship with our own and others’ mortality.” This reductivist urge, which I might also add was largely devoid of narrative, was a radical departure by any measure, but like the electric car in our current age, powerful forces made certain it was not to be, at least not yet. When it did find a foothold in the late 19th century, success was the domain of others.

In the visual arts, a similar reductivism came to inform the boxed works of Johann Dieter Wassmann in the 1890s. Not surprisingly, Johann’s elder brother, Hugo Wassmann, was himself a funerary violinist, as I have mentioned. In her essay, "A Carpenter's Tale," Maime Stombock points out that it was Johann’s sudden and humiliating recognition in 1889 of the depth of his own bourgeois values that long last allowed the fog to lift:

"The final period of work that grew out of these revelations can only be described as early modern. Johann's competence as a carpenter, along with his total command by this point of the medium of the wooden box, allowed him to plunge headlong into works unlike anything he had considered prior. The most striking feature of these pieces is their simplicity of line, plane and form. This new sensibility he referred to by the German expression die Mut zur Lücke -- the courage to leave things out. Several works even verge on abstraction, most notably his politically charged pair KAISER WILHEM II, 1894 and PRINCE OTTO VON BISMARCK, 1896. The enigma of these works, an enigma which creates puzzlement even today, rests in the subtlety of their comment, rather than in the compelling presence of a narrative, as was often the case in earlier works."

READ MORE

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

The Art of Funerary Violin

A post-election day reading from Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (New York: Overlook Press, 2006):

A post-election day reading from Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN (New York: Overlook Press, 2006): “(T)he genre of Funerary Violin evolved in its own distinct manner, following a path of rooted modality and direct expression, and eschewing all displays of virtuosity, in terms of both performance and compositional artistry, in order to explore simply and honestly our relationship with our own and others’ mortality, in all its many and varied historical and cultural aspects. Had it survived until today, who knows how it would have reflected our current disowning of death; however, it is certain that it would have proved more profound and deeply cathartic than the contemporary tendency towards recorded music played on a ghetto blaster. But then maybe a spiritless age deserves a spiritless death. It is not for me to judge.”

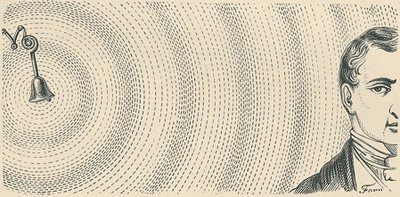

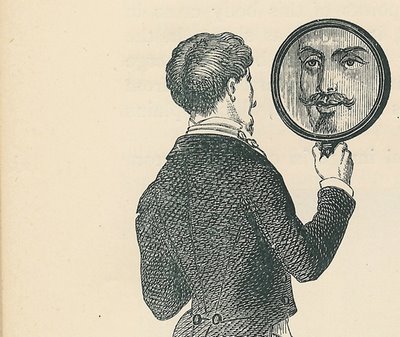

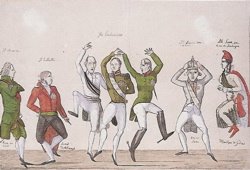

Engraving by J. Forn from the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Music of the Spheres

Johann Dieter Wassmann, HARMONISCH 1895. 145 x 145 x 70 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, HARMONISCH 1895. 145 x 145 x 70 mm.Last week I focused on the composer Hugo Wassmann's involvement with the Guild of Funerary Violinists and the Mizler Society, a theme I don't want to leave just yet, so this week I thought I'd open by looking at the impact of music on Johann Dieter Wassmann's boxed works. Maime Stombock makes the point in her essay, "A Carpenter's Tale," that it was Johann’s friendship with the physicist Max Planck, and their mutual interest in the epistemology of music, that in many ways directed his thinking:

"The late night dialogues Johann records between himself and Planck more often than not centered around music. But then, he was a Leipziger: Wagner, Mendelssohn, Strauss, Liszt, Schumann, Brahms, Grieg, Mahler, they all spent crucial years in the city (as well as in Weimar) during the course of Johann’s life, allowing him to come in contact with each, as well as to see all but Wagner and Schumann either conduct or perform. It would be impossible to overstate the importance of music in his work, despite there being only a handful of direct musical references in his boxes.

"For Johann, music and only music could create such an idealization of space as to transcend time, while still existing within it as an undivided whole. Music is at once truth and form, knowledge and sensation. Music defies absolute space and time by not only transcending the boundaries, but by suggesting the very boundlessness of the universe itself.

"Another to have passed through Leipzig—in this case on his way to Vienna—was Sigmund Freud. In Freud, Johann found his journey had come full circle. Where Johann had begun by challenging his students to question the veracity of truth through his enigmatic displays on human physiology, he ended by proffering that truth is neither supreme nor absolute; our universe may be governed by laws, he suggests, but truth resides just outside our reach, amidst the deepest dark corners of a world we have only just begun to unravel: that of the human mind."

READ MORE

Friday, November 03, 2006

Saxony-Anhalt 1897

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Hugo Wassmann & The Mizler Society

The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN has opened a pandora’s box of questions surrounding Hugo Wassmann’s involvement in the Guild of Funerary Violinists. No less puzzling, however, were Hugo’s ties to the Mizler Society. This late-Baroque musical society was founded by Loren Christoph Mizler von Kolof for the programmatic study of music’s innate relationship to science. Mizler, who attended the University of Leipzig and was a former student of Bach’s, devoted his master's thesis, “Quod musica ars sit pars eruditionis philosophicae,” to the development of a scientific approach to music grounded in mathematics and philosophy. Early members of the society included Bach, Handel and Telemann. Gatherings posed such troubling questions as why parallel fifths were undesirable.

The recent release of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN has opened a pandora’s box of questions surrounding Hugo Wassmann’s involvement in the Guild of Funerary Violinists. No less puzzling, however, were Hugo’s ties to the Mizler Society. This late-Baroque musical society was founded by Loren Christoph Mizler von Kolof for the programmatic study of music’s innate relationship to science. Mizler, who attended the University of Leipzig and was a former student of Bach’s, devoted his master's thesis, “Quod musica ars sit pars eruditionis philosophicae,” to the development of a scientific approach to music grounded in mathematics and philosophy. Early members of the society included Bach, Handel and Telemann. Gatherings posed such troubling questions as why parallel fifths were undesirable.Hugo Wassmann (Johann Dieter Wassmann's next elder brother, pictured dimly here in 1869) was introduced to the then-struggling Mizler Society while studying philosophy at the University of Leipzig. For reasons that are not well understood, Hugo remained a devotee to this antiquated, and decidedly anti-modern, society right up until his death in Weimar in 1915, at the age of 76.

A charming website examining the Mizler Society was recently launched by violinist John Rodgers, so turn up your speakers, click through and enjoy.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Hugo Wassmann & the Guild of Funerary Violinists

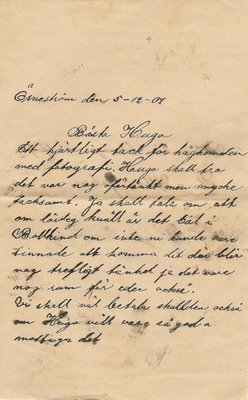

Several correspondents across the Atlantic have, in recent days, raised queries over Hugo Wassmann’s falling out with the Guild of Funerary Violinists in 1901 (last Thursday's post). CRWM, writing on the blog AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS (link below) asks, “Did you not find it interesting that [Rohan Kriwaczek's] AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY failed to mention the irony that brother of one of the greatest proto-modernists was one of the last links to this most pre-modern of traditions?” Indeed, this fraternal relationship is a curious one, but I also find it telling that it was only after Johann’s death in 1898 that Hugo reconsidered his affiliation with the Guild.

Several correspondents across the Atlantic have, in recent days, raised queries over Hugo Wassmann’s falling out with the Guild of Funerary Violinists in 1901 (last Thursday's post). CRWM, writing on the blog AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS (link below) asks, “Did you not find it interesting that [Rohan Kriwaczek's] AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY failed to mention the irony that brother of one of the greatest proto-modernists was one of the last links to this most pre-modern of traditions?” Indeed, this fraternal relationship is a curious one, but I also find it telling that it was only after Johann’s death in 1898 that Hugo reconsidered his affiliation with the Guild. A letter from the noted Swedish music publishers Elin and Ulla Johnson, dated 5 December 1901 and addressed to Hugo, sheds some light on Hugo’s state of mind in coming to what must have been a wrenching decision (above). The letter is currently in the archives of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C. Although written in an old Swedish dialect, I will translate as best I can.

The letter opens thanking Hugo for a photograph (fotographi) he has recently sent them. They then go on to reassure Hugo he has made the right decision in leaving the Guild (def Gál), heartening him with the conviction that the saxophone will one day be the centrepiece of both orchestral and funerary composition, although not necessarily among Lutherans. The letter closes with this encouragement: “The burden is on your shoulders Hugo but God will provide.” It is signed on the reverse, “Elin & Ulla Johnson,” with the added remark, “…send Helge and Eva our love.” Helge and Eva were Hugo’s two surviving daughters.

I hope this sheds further light on the last remaining years of the Guild.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Not a spook, even on Hallowe'en

Must have been the champagne talking, not me; all the same, I do want to apologise to Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann for my wee hours post this morning inadvertently leaving open the possibility of Mr. Wassmann’s involvement with U.S. intelligence. He assures me unreservedly that his State Department stints in Beirut, Istanbul and Nairobi were all in the role of cultural attaché. Here’s our benefactor when we met in Paris a few weeks ago in an effort to finalise agreement for the repatriation to Germany of Johann Dieter Wassmann’s artwork after its 94-year absence.

Must have been the champagne talking, not me; all the same, I do want to apologise to Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann for my wee hours post this morning inadvertently leaving open the possibility of Mr. Wassmann’s involvement with U.S. intelligence. He assures me unreservedly that his State Department stints in Beirut, Istanbul and Nairobi were all in the role of cultural attaché. Here’s our benefactor when we met in Paris a few weeks ago in an effort to finalise agreement for the repatriation to Germany of Johann Dieter Wassmann’s artwork after its 94-year absence.

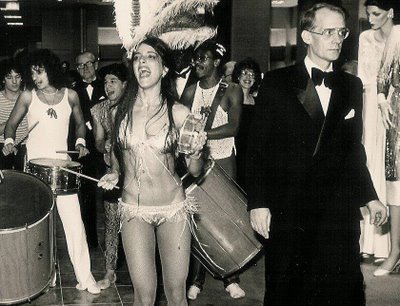

Opening night at the Leipzig Film Festival

Pictured: Countess Eva-Maria von Schönburg-Glauchau at Café Spizz.

Pictured: Countess Eva-Maria von Schönburg-Glauchau at Café Spizz.Leipzig’s glitterati, and then some, gathered last night at the Museum der bildenden Künste for opening celebrations of the city’s annual film festival, Das Internationale Leipziger Festival für Dokumentar- und Animationsfilm, running until 5 November (see link below). Although a poor cousin to the Berlin Film Festival, in focusing on the genres of documentary and animation, the Leipzig festival has found its niche.

As the reluctant subject of THE FOUNDATION, a documentary film currently in production by Australian filmmaker Richard Moore, I’ve been busily booking out the festival season to see what I’m getting myself into.

The evening kicked off with a screening of three powerful films, most notably the short TOWER BAWHER by the Bulgarian digital animator Theodore Usher, who currently lives in Canada. Featuring the score “Time Forward” by Georgy Sviridov, the work sees Russian constructivism deconstructed by the 2nd law of thermodynamics, as entropy rules Usher's universe of line, volume, colour and form.

To the festival organisers' credit, more women directors than ever are represented, but the Eurocentric focus of the directors chosen (if not their subject matter) remains a disappointment.

The usual drinks and chatter followed, with a gracious welcome from mayor Burkhard Junj, before the crowd sprawled out into the chill in search of late-night venues on a sleepy Leipzig Monday. A few years beyond raving, I made my way with the international, but mostly European, contingent to Café Spizz, a local jazz club.

After a grilling over MuseumZeitraum’s American financial backing and a round of questioning over rumours of Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann’s intelligence connections (yes, I believe Mr. Wassmann was formerly with the U.S. Department of State and has some tie to the Kennedy clan; no, he isn’t a spook, to the best of my knowledge), the evening eased into the usual late-night banter covering the war in Iraq, Prof Dr Angela Dorothea Merkel, the sorry state of film funding and, of course, to what extent our Leipzig School painters have ‘gone Faust’.

With first light breaking and the birds a-chirping, I'll say good night for now and keep you posted as the week progresses.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

An Incomplete History of the Art of Funerary Violin

A special thanks to Prairie Lights bookseller Jim Harris for sending along an advance copy of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN. As many of you may know along with Mr. Harris, Johann Dieter Wassmann’s brother, the composer Hugo Wassmann, was active in the Lutheran wing of Leipzig’s Guild of Funerary Violinists in the 1890s. Hugo’s ultimate falling out with the Guild came in 1901 over his efforts to introduce the saxophone to funerary rights, a practice that failed in Leipzig, but would eventually take hold in the city of New Orleans with great success, although not among Lutherans. Meanwhile, the art of funerary violin all but died out in Europe by 1915.

A special thanks to Prairie Lights bookseller Jim Harris for sending along an advance copy of Rohan Kriwaczek’s AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF THE ART OF FUNERARY VIOLIN. As many of you may know along with Mr. Harris, Johann Dieter Wassmann’s brother, the composer Hugo Wassmann, was active in the Lutheran wing of Leipzig’s Guild of Funerary Violinists in the 1890s. Hugo’s ultimate falling out with the Guild came in 1901 over his efforts to introduce the saxophone to funerary rights, a practice that failed in Leipzig, but would eventually take hold in the city of New Orleans with great success, although not among Lutherans. Meanwhile, the art of funerary violin all but died out in Europe by 1915.Here’s a short excerpt from the book’s dust-jacket, and a link if you’re interested in purchasing this intriguing work:

“During the Reformation a new musical form developed to replace Catholic funerary ritual. A solo violinist became central to the conduct of the Protestant funeral. Despite its enormous influence on classical music generally and on the Romantic Movement in particular, this music has almost entirely vanished. In a series of ‘funerary purges’, the violinists were driven into silence or clandestine activity.

“This is a music that, despite all attempts at suppression, has haunted Europe’s collective unconscious for more than a century. Now Rohan Kriwaczek reveals its incredible history. He acts in the hope that by remembering the Guild we realize afresh what our music once was, and what it might be once again.”

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Wednesday Archive #6 - The birth of the modern

The general consensus among academics dates the development of an early modern aesthetic in Johann Dieter Wassmann’s work to 1889. Beyond the presence of modernist concerns in his assemblage works, and later photography, his awareness of the changing nature of art can clearly be seen in his collected ephemera, currently held in the archives of the Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.

The idea that innate images and objects may store substantial metaphorical content is as old as art itself, but it was the modern era that saw their removal from historical context, with essence alone left to both represent and raise doubts about traditional linkages. Johann’s very process of gathering material, either for future works or purely for enjoyment, involved just such a process of removal, stripping away historical ties, opening up potential new meaning for a modern world.

The engraving above is one such image, conjuring a wealth of surreptitious possibilities. Researchers at the foundation have since shown the engraving to be cut from E. Atkinson’s NATURAL PHILOSOPHY (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1887), a translation of A. Ganot's COURS ÉLÉMENTAIRE DE PHYSIQUE, one of several editions Johann owned. The image is, however, nothing more than a demonstration of concave mirrors, but in clipping it from the surrounds of its purpose, he has liberated it, and the viewer, from the historicism of its creation.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Park Sanssouci 1897

JOHANN DIETER WASSMANN, Weinbergterrassen, Park Sanssouci, Potsdam, 1897. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 748030.

As a native Berliner, the arrival of autumn has, since the fall of the wall, beckoned a short trip to Potsdam and a Saturday stroll through the delicious gardens of Sanssouci. This autumn proved no exception, a weekend in Berlin catching shows and openings providing the perfect opportunity to escape to the park’s wonderfully Rococo decadence. The 18th century summer residence of Frederick the Great, Sanssouci is more villa than palace, full of quiet moments of intimacy and folly.

Johann Dieter Wassmann was no less fond of making the trek, although never in summer. Autumn and early spring were his preferred seasons for taking in the brooding melancholy of this most cultured pearl.

Friday, October 20, 2006

The moons of Galileo

"I should disclose and publish to the world the occasion of discovering and observing four Planets, never seen from the beginning of the world up to our own times, their positions, and the observations made during the last two months about their movements and their changes of magnitude; and I summon all astronomers to apply themselves to examine and determine their periodic times, which it has not been permitted me to achieve up to this day . . . On the 7th day of January in the present year, 1610, in the first hour of the following night, when I was viewing the constellations of the heavons through a telescope, the planet Jupiter presented itself to my view, and as I had prepared for myself a very excellent instrument, I noticed a circumstance which I had never been able to notice before, namely that three little stars, small but very bright, were near the planet; and although I believed them to belong to a number of the fixed stars, yet they made me somewhat wonder, because they seemed to be arranged exactly in a straight line, parallel to the ecliptic, and to be brighter than the rest of the stars, equal to them in magnitude . . .When on January 8th, led by some fatality, I turned again to look at the same part of the heavens, I found a very different state of things, for there were three little stars all west of Jupiter, and nearer together than on the previous night.

"I should disclose and publish to the world the occasion of discovering and observing four Planets, never seen from the beginning of the world up to our own times, their positions, and the observations made during the last two months about their movements and their changes of magnitude; and I summon all astronomers to apply themselves to examine and determine their periodic times, which it has not been permitted me to achieve up to this day . . . On the 7th day of January in the present year, 1610, in the first hour of the following night, when I was viewing the constellations of the heavons through a telescope, the planet Jupiter presented itself to my view, and as I had prepared for myself a very excellent instrument, I noticed a circumstance which I had never been able to notice before, namely that three little stars, small but very bright, were near the planet; and although I believed them to belong to a number of the fixed stars, yet they made me somewhat wonder, because they seemed to be arranged exactly in a straight line, parallel to the ecliptic, and to be brighter than the rest of the stars, equal to them in magnitude . . .When on January 8th, led by some fatality, I turned again to look at the same part of the heavens, I found a very different state of things, for there were three little stars all west of Jupiter, and nearer together than on the previous night."I therefore concluded, and decided unhesitatingly, that there are three stars in the heavens moving about Jupiter, as Venus and Mercury around the Sun; which was at length established as clear as daylight by numerous other subsequent observations. These observations also established that there are not only three, but four, erratic sidereal bodies performing their revolutions around Jupiter."

Galileo Galilei, SIDEREUS NUNCIUS, March 1610.

This week I’ve been looking at Johann Dieter Wassmann’s little-known 33-piece suite “Der Ring des Nibelunge,” 1896. Each work in this remarkable ensemble takes the form of a pine box, shaped as an isosceles trapezoid, with the glass front constituting the smaller of the two parallel planes. When assembled in three groups, 11 boxes are positioned to form a circle, with the fronts facing inward, toward one another, rather than outward toward the viewer.

The last of these three groups shows Johann’s strong fascination with an increasingly reductive notion of pure space, space nearing the void of deep space itself. In each of these boxes the sole structural element is one or more planetary forms, but rather than being highly descriptive, these elements are depicted as nothing more than aged brown balls, leaving the focus of our attention on the void itself. The inner surface of these boxes is lined with heavily-stained text, in the case of the work above text from a 19th century French-German dictionary. “The Moons of Galileo” is sufficiently descriptive to allow us to identify the individual moons – from top to bottom, Ganymede, Europa, Callisto and Io – but grouped alone, without Jupiter, they are purposely lost at sea.

This metaphor of complete and possibly abject isolation – the isolation not of the void, but of the individual within the void – came to dominate much of Johann’s output in the remaining 18 months of his life.

Thursday, October 19, 2006

The birth of the surreal

As spring 1896 moved on to summer, Johann Dieter Wassmann continued work on his seminal 33-piece “Der Ring des Nibelunge” (Ring Cycle – please see my previous post for background). During this period the tone of the works turned increasingly playful, covering a range of interests, until a sudden shift arrived with autumn, his final 11 works in the series reaching a dark and deeply introspective spatial void, which I will discuss in my next post. Prior to the void, however, came “The Heavens”, shown above, in which a bird’s nest sprouts not baby birds, but five doll's legs in yet another nod to the Dadaists and Surrealists to come. As cheerful as it is perverse, it brings to mind the eerie 1930s constructions of Hans Bellmer.

As spring 1896 moved on to summer, Johann Dieter Wassmann continued work on his seminal 33-piece “Der Ring des Nibelunge” (Ring Cycle – please see my previous post for background). During this period the tone of the works turned increasingly playful, covering a range of interests, until a sudden shift arrived with autumn, his final 11 works in the series reaching a dark and deeply introspective spatial void, which I will discuss in my next post. Prior to the void, however, came “The Heavens”, shown above, in which a bird’s nest sprouts not baby birds, but five doll's legs in yet another nod to the Dadaists and Surrealists to come. As cheerful as it is perverse, it brings to mind the eerie 1930s constructions of Hans Bellmer.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Privilege of Priests

Following on from my last post, “Of the Stealing of Women,” I thought it appropriate to introduce a companion piece Johann Dieter Wassmann also built in the spring of 1896. Titled “Privilege of Priests,” the construction again begins with an early 18th century law text, this time open to a case law page entitled, Privilege of Priests. But unlike “Of the Stealing of Women,” he removes it from its context, by a adding an engraving of a small boy bandaged from the same mid-19th century medical text as the bandaged women’s torso in “Of the Stealing of Women.” In doing so, the assemblage immediately and painfully evokes the broken children left behind by the unspoken and widely accepted practice of sexual abuse followed for centuries by the Catholic Church. While Johann could best be described as a lapsed Lutheran, we was adamantly anti-Catholic and more than willing to challenge the hypocrisy of the church in works such as this.

Following on from my last post, “Of the Stealing of Women,” I thought it appropriate to introduce a companion piece Johann Dieter Wassmann also built in the spring of 1896. Titled “Privilege of Priests,” the construction again begins with an early 18th century law text, this time open to a case law page entitled, Privilege of Priests. But unlike “Of the Stealing of Women,” he removes it from its context, by a adding an engraving of a small boy bandaged from the same mid-19th century medical text as the bandaged women’s torso in “Of the Stealing of Women.” In doing so, the assemblage immediately and painfully evokes the broken children left behind by the unspoken and widely accepted practice of sexual abuse followed for centuries by the Catholic Church. While Johann could best be described as a lapsed Lutheran, we was adamantly anti-Catholic and more than willing to challenge the hypocrisy of the church in works such as this.Both of these works are drawn from a suite of 33 similarly shaped pine boxes Johann called “Der Ring des Nibelunge,” so-named after Richard Wagner’s “Ring Cycle”. In Johann’s case, the 33 works are divided into 3 groups, with 11 boxes in each. These groups form perfect rings when installed with their glass front facing inward, so the works uniquely face and interact with one another, rather than outward toward the viewer. Johann purchased three round pine champagne tables in the summer of 1896 on which to display the works, but they were never publicly shown in his lifetime. Remarkably “Der Ring des Nibelunge” still has never been displayed as a complete group in a public institution, but will certainly be proudly on display when MuseumZeitraum Leipzig opens in July 2008.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

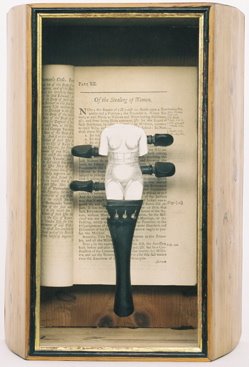

Of the Stealing of Women

Dada and Surrealism were still years away when Johann Dieter Wassmann struck out with this monumental, if misunderstood, work, “Of the Stealing of Women” 1896. Never before published or exhibited, the work merges an early 18th century English case-law text, open to a page describing the (limited) rights of women from being, yes, that’s right, stolen, with a medical engraving of mid-19th century bandaging practices, all linked by a harmony of violin pegs and tailpiece. In his notes on the work, Johann enthusiastically describes the piece in terms that we now might read as empowerment and liberation, closing with an enigmatic quote from his beloved muse, Goethe: ‘Man sieht nur, was man weiss.’ One sees only what one knows. Some critics have hesitated at themes they (mis)read as bondage and repression, with one Australian curator going so far as to have the work removed from the exhibition BLEEDING NAPOLEON at the 2003 Melbourne International Arts Festival (see link below).

Dada and Surrealism were still years away when Johann Dieter Wassmann struck out with this monumental, if misunderstood, work, “Of the Stealing of Women” 1896. Never before published or exhibited, the work merges an early 18th century English case-law text, open to a page describing the (limited) rights of women from being, yes, that’s right, stolen, with a medical engraving of mid-19th century bandaging practices, all linked by a harmony of violin pegs and tailpiece. In his notes on the work, Johann enthusiastically describes the piece in terms that we now might read as empowerment and liberation, closing with an enigmatic quote from his beloved muse, Goethe: ‘Man sieht nur, was man weiss.’ One sees only what one knows. Some critics have hesitated at themes they (mis)read as bondage and repression, with one Australian curator going so far as to have the work removed from the exhibition BLEEDING NAPOLEON at the 2003 Melbourne International Arts Festival (see link below). Personally, I believe the work can be read as a nod to the rising sentiment across Europe in support of women's suffrage. Three years earlier, in 1893, New Zealand was the first country to introduce universal suffrage, generating headlines world-wide. The use of an English case-law book would suggest some reference to the British empire here. The image of a woman bandaged suggests a play on the word suffrage. Violin pegs are, of course, necessary to tune the instrument, implying an adjustment or refinement of the social politic to enhance the role of women in 19th century society.

Whatever its inner meaning, the work stands as a significant precursor to the explosive power Dada and Surrealism would have on the course of 20th century modernism.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

The case of Mlle Marie-Madeleine Lafort Wednesday Archive #05

Amonst the many strange and wonderful dossiers gathered by Johann Dieter Wassmann is an extensive file he kept on the case of Mlle Marie-Madeleine Lafort, a French hermaphrodite whose physical peculiarities were widely studied and published in the mid-19th century (pictured at left in an 1872 engraving by L. Chapon from the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.) Johann's fascination was less voyeuristic than it might at first appear. In the 1890s he became intrigued with the growing debate concerning sexual identity and the determinants that come into play in making us male or female. The case of Mlle Lafort brought into doubt many of society's preconceived notions in this realm.

Amonst the many strange and wonderful dossiers gathered by Johann Dieter Wassmann is an extensive file he kept on the case of Mlle Marie-Madeleine Lafort, a French hermaphrodite whose physical peculiarities were widely studied and published in the mid-19th century (pictured at left in an 1872 engraving by L. Chapon from the collection of The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C.) Johann's fascination was less voyeuristic than it might at first appear. In the 1890s he became intrigued with the growing debate concerning sexual identity and the determinants that come into play in making us male or female. The case of Mlle Lafort brought into doubt many of society's preconceived notions in this realm. The term hermaphrodite has its origins in Greek mythology, named after the son of Hermes and Aphrodite who became joined in one body with the nymph Salmacis. Now known as intersex, this condition of ambiguous genitalia is far more common than is generally assumed, with even the most conservative estimates putting the incidence at 1 in 4500 births. Until the 20th century, the condition was left as is, with parents free to raise the child as they saw fit, but with the rise of modern medicine the fate of the child to become a boy or a girl was most often determined surgically by doctors shortly after birth. For a more enlightened view on the condition and how best to consider the needs of the child, here's a link to Elizabeth Weil's recent piece "What if It’s (Sort of) a Boy and (Sort of) a Girl?" in The New York Times Magazine.

Monday, September 25, 2006

Walt Disney at Le Grand Palais

Johann Dieter Wassmann was a frequent visitor to Naumburg, all the more so after he took to photography in the early 1890s. His fascination with the bold, simple forms of the city’s medieval cathedral are reflected in the large number of images he recorded here over several years. Curiously, the austere geometry of this 13th century Romanesque structure suited his early modernist preoccupation with the reduction of image to line, depth and volumetric form. In the photograph above (WF1070024, albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm), the focus is solely on form, with ornamentation, such as the upper row of stone sculptures, merely incidental.

This ensemble of sculptures just happens to include top-centre-left Count Eckhart and a serene Uta, circa 1245. 40 years after Johann captured this image, Uta would attain far greater attention when Walt Disney combined her carved body with the face of Joan Crawford to create the evil queen in his 1937 adaptation of the Brothers Grimm’s “Snow White”.

Disney’s unbridled confidence in mixing disparate cultural references is now the subject of a major exhibition curated by Bruno Girveau at Le Grand Palais. “Once upon a time, Walt Disney,” which opened last weekend in Paris, honours a man Girveau describes as “one of the great geniuses of the 20th century and the greatest storyteller of the 20th century,” although in a back-handed compliment he goes on to say Disney’s juxtapositions “are completely unscrupulous, something only an American could do, back then and still today.”

For more on the exhibition, and France’s effort to make cultural amends with the U.S., here’s a link to Angela Doland’s overview in The Los Angeles Times.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Mexico City 1897

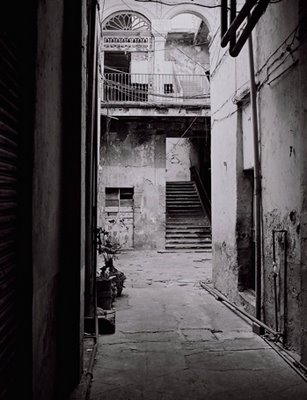

As a pioneer in the field of sewerage management, Johann Dieter Wassmann travelled extensively in Europe, the Americas and the Asia/Pacific. In 1897 he made his final trip, taking in Mexico City, where he consulted with city officials on the ponderous task of devising a gravity sewerage system for a city built at the bottom of a valley in a lake.

Unfortunately, most of his travels were as a younger man, prior to gaining an interest in photography, so they went largely undocumented. By 1897, however, his photographic skills were finely-honed, as was his dexterity with the new hand-held roll film cameras widely available in the 1890s, allowing unprecidented mobility and spontineity for the photographer. Nowhere is this more evident than in his breathtakingly modernist Mexico City portfolio, reminiscent of the early work of Manual Alvarez Bravo. Pictured:

JOHANN DIETER WASSMANN, untitled, Mexico City, 1897. Albumen silver print, 23 x 18 cm, WF 898028.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

A Carpenter's Tale

After yesterday's post several readers have asked where they might learn more about the untimely death of Johann Dieter Wassmann. The best source is Maime Stombock's eloquent essay, "A Carpenter's Tale."

After yesterday's post several readers have asked where they might learn more about the untimely death of Johann Dieter Wassmann. The best source is Maime Stombock's eloquent essay, "A Carpenter's Tale."A CARPENTER'S TALE by Maime Stombock

"At 56, Johann Dieter Wassmann should have known how to board a tram. Clumsy is not a word many would have associated with a man who, as one of Leipzig's foremost civil engineers, led a meticulous life. But in the half light of morning on January 6, 1898, late for a meeting and distracted by the gentle solitude of a new fallen snow, he raced to board a slow moving tram outside his home on the corner of Schonbach and Äuss. Hospital Strasse (now Prager Strasse). With briefcase in hand, he leapt onto the forward running board. As he did, his footing gave way -- he did reach the running board, but missed the handrail and fell backwards, slipping under the carriage. Despite having the wherewithal to roll as he fell he was unable to roll far enough. The rear wheels of the tram, in their deliberate progress, crushed his left leg just below the knee, leaving a stump with a dangling calf and booted foot secured only by his few remaining calf muscles.

"But Johann Dieter Wassmann wasn't clumsy, as I have said. He was in a hurry. Herein lies the none-too-subtle irony in his death from these injuries three months later: It was the very pace of modern life and man's obsession with time, at the expense of the wonder of the space around him, that had come to preoccupy Johann's personal and creative life in the closing decade of the 19th century, although it was his more celebrated professional life that had given him pause to ask: where is it all going? Renowned in the burgeoning field of sewerage management, he had experienced the toll of industrialization and urbanization first-hand. But he did more than just experience it; he spent the whole of his illustrious career battling to thwart this dual assault on the human condition..."

READ MORE

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Wednesday Archive #04 - Dein goldenes Haar...

In addition to the extensive personal archives of Johann Dieter Wassmann housed at The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C., there is a small but curious collection of articles the family gathered in the months after the artist's death on March 18, 1898. One such item is this tiny lock of the artist's hair, lovingly bound with red thread, framed here by the envelope of his death notice. The cause of death was a streptococci infection that developed after the artist slipped on ice and fell under a slow moving tram on January 6, 1898. His right leg was crushed, requiring amputation, but an infection soon developed in hospital and he was never to recover.

In addition to the extensive personal archives of Johann Dieter Wassmann housed at The Wassmann Foundation, Washington, D.C., there is a small but curious collection of articles the family gathered in the months after the artist's death on March 18, 1898. One such item is this tiny lock of the artist's hair, lovingly bound with red thread, framed here by the envelope of his death notice. The cause of death was a streptococci infection that developed after the artist slipped on ice and fell under a slow moving tram on January 6, 1898. His right leg was crushed, requiring amputation, but an infection soon developed in hospital and he was never to recover.

Friday, September 15, 2006

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Neo Rauch: 'Der Zeitraum'

Last week I offered up a range of posts in the lead-up to Neo Rauch's September 9 'Der Zeitraum' opening, including a review on opening day, but I wasn't yet able to show you the paintings themselves. Well here's a link to the complete catalogue, courtesy Galerie Eigen + Art Leipzig. The link opens a PDF file, so you may have to be a little patient.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Wednesday Archive #03 - Galvani's Experiment, 1790

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Stasi Museum Leipzig

September 11, 2006 gave me pause to reflect on the chilling return of authoritarian and fascist ideologies, from both within and without, and our general inability as an art community to respond to these threats in any meaningful way. One rare exception can be found in the Museum of Modern Art’s recently opened exhibition ‘Out of Time’ in New York. Amidst the clutter of this effort to display the museum’s contemporary collection is the haunting four-screen video projection work ‘Stasi City’ (1997) by the British artists Jane and Louise Wilson. Here’s how Roberta Smith describes the work in The New York Times: "'Stasi City,’ takes us on a clanging, Cubist tour of the abandoned headquarters of East Germany’s secret police. This symbol of daunting power becomes a readymade. Relentless tracking shots and dumbwaiters used to disorienting effect move us up, down and through the building, along endless hallways, into office-like interrogation chambers (note the padded doors), past revolving file boxes once filled with dossiers. The dead-end is a room for medical examinations, surgery or perhaps torture. Its floor is littered with blue and white flakes of peeled paint that evoke a vast Arctic ice pack. With its mordant slapstick, ‘Stasi City’ may be a structuralist version of ‘Dr. Strangelove,’ but it undercuts tragedy with the suggestion that evil ultimately crumbles and falls away. And its formal rigor is itself cause for hope.”

More daunting still, see the real thing. There are Stasi Museums in former Stasi headquarters in both Leipzig and Berlin. Each museum has a thoughtful website worth further reflection; I’ve included a link below to the site here in Leipzig. Dittrichring 24; 14:00-18:00 Wednesday to Sunday; admission free.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Neo Rauch at Eigen + Art Leipzig

In 1908, Hermann Minkowski gave a lecture in Cologne on the world-view his former student, Albert Einstein, was implicating by his special theory of relativity, published three years earlier. Minkowski began the lecture with the proclamation that, “Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.”

In 1908, Hermann Minkowski gave a lecture in Cologne on the world-view his former student, Albert Einstein, was implicating by his special theory of relativity, published three years earlier. Minkowski began the lecture with the proclamation that, “Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.” Today's opening of 'Der Zeitraum' at Galerie Eigen + Art Leipzig attests that the paintings of Neo Rauch have moved full force into just such an independent reality. Surrounded by friends and family on a day with the first hint of autumn in the air, the artist could not have chosen a more germane moment in which to solidify themes he has been patiently moving toward for several years. Neo’s show at David Zwirner/New York last year gave clear indication that the artist was leaving behind the social realist iconography of the GDR - imagery that had made him a household name in the global art market - finding his own private Idaho within a more expansive landscape of memory.

In the March 2001 issue of ArtForum, Daniel Birnbaum wrote of Neo’s work at the time, "This is a weirdly concrete dream of production, athletic strength, and socialist modernity dreamed in a time and a place that no longer exists." That was then; this is now. As the exhibition title implies, ‘Der Zeitraum’ suggests a moment in space and time that very much exists, eternally and universally, a time in which past, present and future both co-exist and are carried concurrently with the temporal experience of the everyday.

That’s not to say these monumental paintings don’t establish location (Ortung); they do and that place is very much Neo’s native Saxony. The landscape of memory this implies is therefore one ensconced in the landscape of eastern Germany, but with the passing of years it is no longer one so focused on the recent experience of the GDR, which, as Birnbaum rightly suggests, doesn’t exist any longer. Rather, Neo’s canvases now embrace a comprehensive landscape, encapsulating the history and experience of modernity itself.

Where and when the modern era began may be open to debate, but there is little doubt it was in full swing by the close of the Napoleonic Wars. Here Leipzig holds unique memory, as host and victim of the single bloodiest struggle in European history prior to the First World War – the Battle of Leipzig (1813). This birth of the modern era from the very blood of Leipzigers is uppermost in the city’s collective memory and recurrent in Neo's imagery of Napoleonic-era figures in recent paintings such as ‘Neujahr’ and ‘Schmerz’ (shown at Zwirner).

As a pinnacle of modern thinking, Einstein’s special theory debunked Newtonian notions of fixed space and time in its conclusion that the perception of space and time differ according to the unique position of the observer. With ‘Der Zeitraum’, Neo Rauch has made a bold, elegant and decisive argument that our perception of modernity likewise hinges on the unique perspective collective memory affords the viewer.

To give Neo the last word, "Some people... detect Americanism in my work; others think it's Far Eastern; and only the spiteful fellow painter who lives in the next village recognizes my paintings to be nothing other than the same provincial manure he has in front of his own nose."

Pictured:

1. by the author, 'Russenstraße', Leipzig, 2006, colour photograph.

2. Johann Dieter Wassmann, 'Quedlinburg', 1895, albumen silver print.

3. artist unknown, 'Le Congrés' (The Congress of Vienna), 1815, colour etching.

9 September 2006 through 22 December 2006

Galerie Eigen + Art

Spinnereistraße 7, Halle 5 D-04179 Leipzig

Opening hours: Tuesday through Saturday: 11:00 - 18:00

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)