Saturday, November 03, 2007

One last look

The announcement on Thursday that an agreement has been reached with the Wassmann Foundation that will see the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann repatriated to Germany has been met with overwhelming joy here in Leipzig (see official statement below). Before the works leave the United States, however, here's one last look at these beloved pieces in situ, as they have appeared for the last quarter century at the Wassmann Foundation's Washington, D.C. headquarters. Our tour is graciously led by Kaufmann Director Jeffrey D. Wassmann.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Museum reaches landmark repatriation accord

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Washington, D.C., November 1, 2007 — Announcing a "new page of cooperation," MuseumZeitraum Leipzig and the Wassmann Foundation today signed a watershed accord under which the foundation will return over 100 nineteenth century assemblage works by the early modernist Johann Dieter Wassmann (1841-1898). For the past decade the artist’s Leipzig descendants have argued these works were removed in 1912 from storage in Weimar without their knowledge, consent or agreement.

In exchange for yielding the works to the Saxon museum — including the prized 33-work Der Ring des Nibelungen (Ring Cycle) 1895-1897 — the foundation will retain the artist’s large trove of photographic works and continue to oversee conservation. The foundation will also provide financial assistance for completion of a new home for the museum opening in July 2008.

At a joint news conference at the foundation’s Washington, D.C. headquarters, Kaufman Director Jeffrey D. Wassmann said the agreement "corrects the misunderstandings and errors committed in the past."

It will "pave the road to new legal and ethical norms for the future," he added. At the same time, Mr. Wassmann said, the accord "opens a new phase of collaboration which does not deprive the many visitors to our foundation of the opportunity to experience Johann’s legacy."

The pact, the first of its kind between an American foundation and a German museum, is being hailed as a model for settling repatriation disputes involving other Western arts institutions.

"Germany has won, the Wassmann Foundation hasn't lost, and what has benefited is culture," MuseumZeitraum’s director, Sophie Vogt, said at the signing ceremony.

Under the terms of the accord, the Wassmann Foundation will return a total of 115 works to Germany, among them Arteriae Pelvis, Abdomimis, et Pectoris, 1883, The Case of the City of London 1894, 16969, 1896, Vorworts! 1897, and the much-loved Nietzsche 306P 1897.

The works were shipped from Weimar to the Port of Baltimore in 1912 by the artist’s son-in-law, Edward Liszt, where they were taken into the care of Johann’s nephews, Friedrich, Dieter and Henry Wassmann. The works remained in storage, first in Washington, D.C. and later in Harrisburg, PA until 1969, when the foundation was established in the will of Gladys Wassmann. Since that time, the estate has been solely governed by the Wassmann Foundation, a role that will now be jointly shared by the two institutions.

Family members in Leipzig had long believed the works were destroyed in World War II, only becoming aware of their continued existence in the early 1990s after the reunification of Germany.

Of the works that will remain in Washington, Mr. Wassmann said, "The photographs of Johann Dieter Wassmann provide the missing link between the meticulous, but still largely prescriptive street imagery of mid-19th century photographer Charles Marville, and the lyrical melancholy of Eugene Atget in the early 20th century. As a predecessor to his fellow countrymen Heinrich Zille and August Sander, Johann discreetly anticipated what vast potential the photographic arts held for the modernist era."

Ms. Vogt commented that, “The restitution of the works represents the healing of a wound. We are grateful to the Wassmann Foundation for safekeeping and conserving these works, but it is now time for them to come home.”

"This is another step forward," she said of the agreement. "But Leipzig must also hold up its own end by seeing that the doors of MuseumZeitraum open wide in July 2008 to Johann’s many passionate admirers on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Washington, D.C., November 1, 2007 — Announcing a "new page of cooperation," MuseumZeitraum Leipzig and the Wassmann Foundation today signed a watershed accord under which the foundation will return over 100 nineteenth century assemblage works by the early modernist Johann Dieter Wassmann (1841-1898). For the past decade the artist’s Leipzig descendants have argued these works were removed in 1912 from storage in Weimar without their knowledge, consent or agreement.

In exchange for yielding the works to the Saxon museum — including the prized 33-work Der Ring des Nibelungen (Ring Cycle) 1895-1897 — the foundation will retain the artist’s large trove of photographic works and continue to oversee conservation. The foundation will also provide financial assistance for completion of a new home for the museum opening in July 2008.

At a joint news conference at the foundation’s Washington, D.C. headquarters, Kaufman Director Jeffrey D. Wassmann said the agreement "corrects the misunderstandings and errors committed in the past."

It will "pave the road to new legal and ethical norms for the future," he added. At the same time, Mr. Wassmann said, the accord "opens a new phase of collaboration which does not deprive the many visitors to our foundation of the opportunity to experience Johann’s legacy."

The pact, the first of its kind between an American foundation and a German museum, is being hailed as a model for settling repatriation disputes involving other Western arts institutions.

"Germany has won, the Wassmann Foundation hasn't lost, and what has benefited is culture," MuseumZeitraum’s director, Sophie Vogt, said at the signing ceremony.

Under the terms of the accord, the Wassmann Foundation will return a total of 115 works to Germany, among them Arteriae Pelvis, Abdomimis, et Pectoris, 1883, The Case of the City of London 1894, 16969, 1896, Vorworts! 1897, and the much-loved Nietzsche 306P 1897.

The works were shipped from Weimar to the Port of Baltimore in 1912 by the artist’s son-in-law, Edward Liszt, where they were taken into the care of Johann’s nephews, Friedrich, Dieter and Henry Wassmann. The works remained in storage, first in Washington, D.C. and later in Harrisburg, PA until 1969, when the foundation was established in the will of Gladys Wassmann. Since that time, the estate has been solely governed by the Wassmann Foundation, a role that will now be jointly shared by the two institutions.

Family members in Leipzig had long believed the works were destroyed in World War II, only becoming aware of their continued existence in the early 1990s after the reunification of Germany.

Of the works that will remain in Washington, Mr. Wassmann said, "The photographs of Johann Dieter Wassmann provide the missing link between the meticulous, but still largely prescriptive street imagery of mid-19th century photographer Charles Marville, and the lyrical melancholy of Eugene Atget in the early 20th century. As a predecessor to his fellow countrymen Heinrich Zille and August Sander, Johann discreetly anticipated what vast potential the photographic arts held for the modernist era."

Ms. Vogt commented that, “The restitution of the works represents the healing of a wound. We are grateful to the Wassmann Foundation for safekeeping and conserving these works, but it is now time for them to come home.”

"This is another step forward," she said of the agreement. "But Leipzig must also hold up its own end by seeing that the doors of MuseumZeitraum open wide in July 2008 to Johann’s many passionate admirers on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

MuseumZeitraum Leipzig

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity?

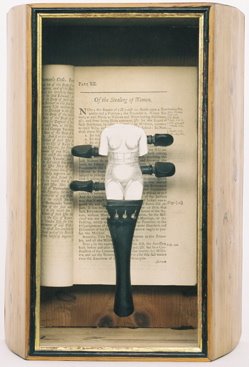

Dada and Surrealism were still years away when Johann Dieter Wassmann struck out with this monumental, if misunderstood, work, “Of the Stealing of Women” 1896. Never before published or exhibited, the work merges an early 18th century English case-law text, open to a page describing the (limited) rights of women from being, yes, that’s right, stolen, with a medical engraving of mid-19th century bandaging practices, all linked by a harmony of violin pegs and tailpiece. In his notes on the work, Johann enthusiastically describes the piece in terms that we now might read as empowerment and liberation, closing with an enigmatic quote from his beloved muse, Goethe: ‘Man sieht nur, was man weiss.’ One sees only what one knows. Some critics have hesitated at themes they (mis)read as bondage and repression, with one Australian curator going so far as to have the work removed from the exhibition BLEEDING NAPOLEON at the 2003 Melbourne International Arts Festival.

Dada and Surrealism were still years away when Johann Dieter Wassmann struck out with this monumental, if misunderstood, work, “Of the Stealing of Women” 1896. Never before published or exhibited, the work merges an early 18th century English case-law text, open to a page describing the (limited) rights of women from being, yes, that’s right, stolen, with a medical engraving of mid-19th century bandaging practices, all linked by a harmony of violin pegs and tailpiece. In his notes on the work, Johann enthusiastically describes the piece in terms that we now might read as empowerment and liberation, closing with an enigmatic quote from his beloved muse, Goethe: ‘Man sieht nur, was man weiss.’ One sees only what one knows. Some critics have hesitated at themes they (mis)read as bondage and repression, with one Australian curator going so far as to have the work removed from the exhibition BLEEDING NAPOLEON at the 2003 Melbourne International Arts Festival. Personally, I believe the work can be read as a nod to the rising sentiment across Europe in support of women's suffrage. Three years earlier, in 1893, New Zealand was the first country to introduce universal suffrage, generating headlines world-wide. The use of an English case-law book would suggest some reference to the British empire here. The image of a woman bandaged suggests a play on the word suffrage. Violin pegs are, of course, necessary to tune the instrument, implying an adjustment or refinement of the social politic to enhance the role of women in 19th century society.

Whatever its inner meaning, the work stands as a significant precursor to the explosive power Dada and Surrealism would have on the course of 20th century modernism.

Sunday, July 08, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity? What is bare life?

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Nietzsche 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Nietzsche 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.In recent posts I've been examining the first of three leitmotifs posed by the Documenta 12 team, "Is modernity our antiquity?" If I may, I'd like to skip ahead to the second question for a moment, "What is bare life?" as further means of addressing the first.

In 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown, often attributed to his contraction of syphilis, resulting in his admission to various clinics before he was moved to Naumburg, where his mother looked after him until her death in 1897. At this point his sister Elisabeth shifted him to Weimar, where she continued his care, as well as promoting his legacy and allowing the occasional audience with guests until his death in 1900.

It was in Weimar that Johann Dieter Wassmann briefly visited Nietzsche, but finding only a shell of a man he returned home to produce this work, depicting simply and eloquently the empty collar of the man, an organ stop with the name 'Nietzsche' printed on it, and an opium-stained bone apothecary spoon; a life stripped bare. These objects are placed against a dappled blue wall, reflecting Nietzsche's penchant for blue-lensed spectacles.

Johann's ability to take the contemporary moment of his visit with Nietzsche and so confidently convert it into the iconography of modernism speaks legions about the raw vitality of the modern movement at the dawn of the 20th century. In no time, however, modernity fell victim to the second law of thermodynamics, with entropy holding sway, but it was not until the close of the century that we realised the paradigm had simply collapsed en route.

Today it is essentially modernity stripped bare that we address as artists and curators, an ongoing post-mortem of abject failure. So in this sense is modernity our antiquity? The answer is not so clear.

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

Documenta 12 takes a beating.

After being savaged by the English-language press earlier in the month, Documenta 12 has now been ravaged by the elements, with Ai Weiwei's Template collapsing in high winds last week. In more recent days, the Plastic Palace has failed to keep Kassel's heavy rains out with roof vents found to be faulty and refusing to close (although we are happy to report there have been no fatalities of either art or art lovers, excluding Template, that is). On low land near the river, the Aue Pavilion is fast becoming the Eau Pavilion, so bring your Wellington boots if you're planning to visit anytime soon. With 90 days to go, let's hope the rest holds together for late arrivals.

After being savaged by the English-language press earlier in the month, Documenta 12 has now been ravaged by the elements, with Ai Weiwei's Template collapsing in high winds last week. In more recent days, the Plastic Palace has failed to keep Kassel's heavy rains out with roof vents found to be faulty and refusing to close (although we are happy to report there have been no fatalities of either art or art lovers, excluding Template, that is). On low land near the river, the Aue Pavilion is fast becoming the Eau Pavilion, so bring your Wellington boots if you're planning to visit anytime soon. With 90 days to go, let's hope the rest holds together for late arrivals. Is modernity our antiquity? Well, the ruins of Documenta 12 would certainly suggest as much.

.jpg)

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

The Zeitraum gardens

Work continues at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig toward our mission of opening to the public next summer. This week the foundations went in for our garden terrace. The terrace is a tribute to one of Johann's best known works, his photograph of the Freundschaftstempel in Potsdam, 1896 (below).

Work continues at MuseumZeitraum Leipzig toward our mission of opening to the public next summer. This week the foundations went in for our garden terrace. The terrace is a tribute to one of Johann's best known works, his photograph of the Freundschaftstempel in Potsdam, 1896 (below). Frederick the Great had this small, elegant temple built in 1768 in memory of his sister, Wilhemine of Bayreuth by Gontard, according to his own sketches and plans. It was modelled on the Temple of Apollo in the Amalthea garden at Neuruppin, court architect Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff's first work.

Is modernity our antiquity? Hmmm... the lines blur!

JOHANN DIETER WASSMANN, Freundschaftstempel, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 743020.

JOHANN DIETER WASSMANN, Freundschaftstempel, Potsdam, 1896. Albumen silver print, 18 x 23 cm, WF 743020.

Sunday, June 17, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity?

Earlier this evening I was delighted to bump into curator Abigail von Bibera at Documenta 12's Museum Fridericianum. Over drinks she made the observation that the creative process behind Hazoume Romould's African 'masks'(see below) struck her as remarkably similar to the thinking that must have gone into Johann Dieter Wassmann's Prince Otto von Bismarck, 1896, pictured here. Good spot Abigail. Which again raises the question, is modernity our antiquity? Or as I discussed in an earlier blog, is it just our Hotel California?

Earlier this evening I was delighted to bump into curator Abigail von Bibera at Documenta 12's Museum Fridericianum. Over drinks she made the observation that the creative process behind Hazoume Romould's African 'masks'(see below) struck her as remarkably similar to the thinking that must have gone into Johann Dieter Wassmann's Prince Otto von Bismarck, 1896, pictured here. Good spot Abigail. Which again raises the question, is modernity our antiquity? Or as I discussed in an earlier blog, is it just our Hotel California?

Saturday, June 16, 2007

First Look: Hazoume Romuald @ Documenta 12

The morning after the night before.

With revelers still wandering the streets of Kassel from the opening party last night, Documenta 12 is just a few hours away from officially opening to the public. Here's a photo op from earlier in the week of the artists selected for this year's event. I've uploaded a fairly large file, so click on it to enlarge if you want to better see who's who. While I managed a sneak preview of several venues yesterday, Walter Robinson has written quite a comprehensive piece for ArtNet so click through for his first impressions and I'll fill you in with more in the coming days.

With revelers still wandering the streets of Kassel from the opening party last night, Documenta 12 is just a few hours away from officially opening to the public. Here's a photo op from earlier in the week of the artists selected for this year's event. I've uploaded a fairly large file, so click on it to enlarge if you want to better see who's who. While I managed a sneak preview of several venues yesterday, Walter Robinson has written quite a comprehensive piece for ArtNet so click through for his first impressions and I'll fill you in with more in the coming days.

Thursday, June 14, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity? The answer is nigh.

Documenta 12 doesn't officially open till the weekend, but a number of works have been erected in public spaces here in Kassel and they're already drawing interest from locals and early arrivals. This afternoon I ran out to have a look at Shipwreck and Workers (version 3) (pictured) by Allan Sekula at the Herkules (mentioned in my last post). The work comprises a progression of large photograghs, several of which can be seen here to right of the Wasserspiel. Sekula hails from Erie, PA and was also heavily featured in Documenta 11.

Documenta 12 doesn't officially open till the weekend, but a number of works have been erected in public spaces here in Kassel and they're already drawing interest from locals and early arrivals. This afternoon I ran out to have a look at Shipwreck and Workers (version 3) (pictured) by Allan Sekula at the Herkules (mentioned in my last post). The work comprises a progression of large photograghs, several of which can be seen here to right of the Wasserspiel. Sekula hails from Erie, PA and was also heavily featured in Documenta 11. Unfortunately, the rain that plagued the opening days of the Venice Biennale seems to have followed the art mob north and moments ago began bucketing down in droves as I waited for my tram back into town from Schloss Wilhelmshöhe. With more of the same forecast throughout the weekend, let's hope King Roger's Plastic Palace isn't made of cotton candy.

Blackberry permitting, I'll duly keep you posted. Tschüss.

Tuesday, June 12, 2007

1 down, 2 to go.

As the art hoards head north from Venice to Basel this week, the citizens of Kassel are enjoying one last moment of calm before the onslaught begins on their own city, with the opening of Documenta 12 this weekend.

As the art hoards head north from Venice to Basel this week, the citizens of Kassel are enjoying one last moment of calm before the onslaught begins on their own city, with the opening of Documenta 12 this weekend. Several readers have asked advice on what else there is to do in Kassel beyond Documenta, with the standard reply being, "Nothing," but I beg to differ. Kassel's museums offer a cabinet of curiosities well worth pursuing when you need a break from the newest and latest at Documenta. While The German Wallpaper Museum may not be to everyone's liking, the home of the Brothers Grimm is a short walk from main Documenta venues, offering a welcome respite. Across the street from the Grimms is the Neue Gallery, featuring perhaps Joseph Beuys best known work, The Pack, 1969 (above), as well as many landmark German paintings from the late 20th century.

Even closer to Documenta is the rather fabulous Museum of Natural History in the Ottoneum. You'll pass it daily walking from the Museum Fridericianum to L'Orangerie, but few of Document's 650,000 viewers will ever step into this marvelous little museum of wonders.

Also worth a diversion is Schloss Wilhelmshöhe on the edge of town, which houses the Old Masters Gallery. Choose a Wednesday or Sunday and you'll experience one of the great marvels of eighteenth century mechanical engineering, as you watch the Wasserspiel cascade down the mountain in it's half hour trek from the Herkules statue on the summit, finishing in a 52 meter jet of water in the gardens of the Schloss.

Unlike Venice and Basel, opening night in Kassel is a public event, with a grand party for the entire city kicking off Friday night.

Is modernity our antiquity? Finally, we'll learn the truth according to Roger & Ruth this weekend. See you there.

Monday, May 21, 2007

Zeitraum Rising

I've just realised I haven't given you an update on MusesumZeitraum's progress in some time. Too busy debating the great issues. Here's a shot of Klaus Richter in the Leipzig foundry where our fabulous new staircase is being fabricated. When installed, this sculptural wonder will lead up from the ground floor galleries to the photographic rooms.

I've just realised I haven't given you an update on MusesumZeitraum's progress in some time. Too busy debating the great issues. Here's a shot of Klaus Richter in the Leipzig foundry where our fabulous new staircase is being fabricated. When installed, this sculptural wonder will lead up from the ground floor galleries to the photographic rooms. Is modernity our antiquity? Not at MuseumZeitraum, where modernity remains the order of the day.

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

When men were men and Beuys was Beuys. Documenta 12 enjoys the shade of D7.

With the opening of Documenta 12 just a month away, I ventured out west to Kassel last week to visit King Roger and Queen Ruth and gaze upon their majestic new Plastic Palace on the grounds of L’Orangerie. If you don’t mind the distant roar of generators and compressors keeping the air conditioning flowing, and you ignore the implications for Documenta 12’s carbon footprint, it’s a spectacular sight, even without the art installed.

With the opening of Documenta 12 just a month away, I ventured out west to Kassel last week to visit King Roger and Queen Ruth and gaze upon their majestic new Plastic Palace on the grounds of L’Orangerie. If you don’t mind the distant roar of generators and compressors keeping the air conditioning flowing, and you ignore the implications for Documenta 12’s carbon footprint, it’s a spectacular sight, even without the art installed.It is not possible in my experience, however, to visit Kassel without feeling the overwhelming presence of an installation that returns to life this time every year, that of Joseph Beuys 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks). Planting of the trees began at Documenta 7 in 1982 and continued for five years with support from the Dia Foundation, with the last of the 7000 planted at D8.

25 years on, the oaks are reaching a more graceful maturity than most of us. And hopefully, with the buds open and the leaves growing to fullness this month, Prince Joseph’s grand gesture will be busy converting King Roger’s carbon dioxide output back into fresh clean oxygen.

One of my favourite gifts for artist friends is to pass along a handful of acorns from these sacred oaks after a trip to Kassel. I’ve even been known to hop off the train to spend an hour collecting acorns before jumping on the next train when my travels take me through Kassel. This year I loaded up a shoe-box full from around the University and have been busy wrapping them up and posting them out. The notion of the artist’s seed spreading across the globe even after death is terribly modernist, I know, but all credit to Prince Joseph for such a far-sighted effort.

Is modernity our antiquity? In this case, sadly yes. What is bare life? Prince Joseph’s seed – the acorn – I believe. Was tun? Plant trees, King Roger, to repent for your sins!

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

"Controversy is normal with us"

Documenta 12 artistic director Roger M. Buergel offers members of the press a guided tour of exhibition venues earlier today in Kassel.

Documenta 12 artistic director Roger M. Buergel offers members of the press a guided tour of exhibition venues earlier today in Kassel. Buergel made clear he has won the argument with architect Jean Philippe Vassal that I've been reporting on in recent days and the Plastic Palace will be fully air conditioned. Roger pointedly told the press, "The architecture has to subordinate itself to the art." As to such high-brow concerns as his leitmotif, Is modernity our antiquity? we'll get back to that after the gossip dies downs.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

Documenta 12: better pack your Hawaiian Tropic

Last week I gave you a first look at the new Plastic Pavilion rising before Kassel’s Orangerie for Documenta 12 this summer. This week I can confirm rumours circulating around the city that artistic director Roger Buergel isn’t altogether happy with the pavilion's architects, Jean-Philippe Vassal and Anne Lacaton.

Last week I gave you a first look at the new Plastic Pavilion rising before Kassel’s Orangerie for Documenta 12 this summer. This week I can confirm rumours circulating around the city that artistic director Roger Buergel isn’t altogether happy with the pavilion's architects, Jean-Philippe Vassal and Anne Lacaton. Die Süddeutsche Zeitung is running an interview with the French team today in which they take the position that the structures should live and breathe Kassel's natural climate. Roger's not so sure.

"The problem is not the form of the pavilion," explains Vassal. "It's the system. One should feel the atmosphere of fresh air in the [Karlsaue] park, close to the river. In the summer, the Karlsaue should become a resting place that is as natural as possible and understood as part of the exterior. The climate should be felt inside, too, in a way that's different from the traditional museum. . . A greenhouse should not be sealed off."

Buergel, on the other hand is panicking that hanging art works -- many on loan from institutional collections -- in a hot and sweaty greenhouse all summer may not make him the most popular director among conservation staff. Word has it there are already threats of works being pulled from the show.

The architects argue the system meets Buergel's concept of an India-inspired "palm grove" where guests can congregate and discuss art and society, while Buergel is insisting his metaphor is being taken a little too far.

"The most important factor for the museum climate is the sweat of each individual visitor," Vassal says. "There, a purely artificial atmosphere becomes a problem. If Buergel has an image in mind of people sitting under trees in India, then he should think about what kind of architecture comes closest to this image."

Is modernity our antiquity, Roger asks? It will be soon enough if he starts shipping home Ruschas and Richters left faded, blistered and cracking from a summer in the sun.

Monday, April 23, 2007

Was tun? A way forward.

Over the past two months I've been deliberating Documenta 12's leitmotif, Is modernity our antiquity? I've argued that both modernity and antiquity are little more than linear, if substantial, events in the West's ongoing Terror of History. This terror has now engulfed all the world's reaches, but there are those still defiant in their determination not to sink into the cultural morass that is the West's making. I offered the example of Aboriginal Australia, one culture whose preoccupation with place has allowed them to maintain a certain remove from this Terror of History and from the all-consuming linearity of time.

A performance staged last month at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, offers perhaps the most compelling way forward, one involving neither modernity, nor antiquity, but an acceptance of the Aboriginal world-view transcendent of time, fixated rather on the universality of space. Here several of Australia's leading jazz musicians perform traditional manikay (song) with songmen from the Ngukurr community, along the Roper River in south-east Arnhem Land. In singing the songs of their ancestors, songs whose origins anthropologists date back some 40,000 years, these songmen and their jazz cohorts join together to renew the very birth of our human existence, a humbling and thought-provoking thing to experience, even if only on YouTube.

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

Documenta 12 wonders, is modernity our antiquity? Yes, and we have Andy and GoogleNation to thank.

Regular readers will notice several changes in our blog over the past week, with the inclusion in our right-hand column of a live news diary covering breaking events in the art world, and rotating videos relating to both Leipzig and the art scene at large. These are brought to you courtesy of Google and YouTube. The news pre-set is for stories on documenta 12, but you can click on any of the other listed keywords, including biennale, louvre and museumzeitraum to find out what's happening in these worlds.

In the lead-up to Documenta this summer, we've been discussing Roger and Ruth's leitmotifs, is modernity our antiquity?, what is bare life? and was tun?

One of my contentions has been that the breakdown of modernity has come about through the collapse of its power structures, mostly recently and most significantly through the rise of the internet. Constantly evolving technologies such as these services all contribute to an increase in the reach and voice of the individual at the expense the traditional gatekeepers of the canon, creating a certain paradox: in a mass global society, the power and importance of the individual grows, rather than diminishes. For individuals in what were formerly the planets outer reaches, the web has democratised access to the structures and machinations of power to an extent previously unimagined. Little more than 20 years after the art world 'discovered' there was an 'outside' and 'periphery', they've suddenly found it's gone. With the playing field flattened in our postcolonial/internet age, there is only the centre to be fought over and for the artist, the ensuing chaos to decipher. Where once the internet merely informed the political process, it now has the immense capability of wholly transforming it.

Thursday, April 12, 2007

Documenta 12 rises before the Orangerie

With all our talk of Documenta 12's leitmotifs in recent weeks - Is modernity our antiquity? What is bare life? Was tun? - it's easy to forget there's real work being done to ready Kassel for the grand opening, just two months away. Here's a first look at the temporary galleries, or Plastic Palace as it's being called, on the beautiful grounds of the Orangerie.

With all our talk of Documenta 12's leitmotifs in recent weeks - Is modernity our antiquity? What is bare life? Was tun? - it's easy to forget there's real work being done to ready Kassel for the grand opening, just two months away. Here's a first look at the temporary galleries, or Plastic Palace as it's being called, on the beautiful grounds of the Orangerie.

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

Documenta 12 asks, “Is modernity our antiquity?” MZL wonders, maybe it’s rocket science after all.

Three years after the publication of Albert Einstein’s seminal Special Theory of Relativity (1905), his mentor and one-time teacher, Hermann Minkowski, gave a lecture in Cologne elaborating on his former student’s findings, beginning with the proclamation that,

Three years after the publication of Albert Einstein’s seminal Special Theory of Relativity (1905), his mentor and one-time teacher, Hermann Minkowski, gave a lecture in Cologne elaborating on his former student’s findings, beginning with the proclamation that, Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.

What Minkowski couldn’t predict was how painfully long it would take for our Newtonian belief in fixed time to actually fade into mere shadows. As the twentieth century unfolded, fixed time only became more entrenched, largely because it proved so useful a tool in promoting our singular march toward Progress.

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, there are cultures for whom space and time never suffered the humiliation of separation, Aboriginal Australia chief among them. Here the Dreaming maintains a union of the two, where there is only place to consider.

Einstein would seem to concur, once stating, “The distinction between past, present and future is only an illusion, even if a stubborn one.” To remove Einstein’s theory from the theoretical and prove it, of course, meant doing things like sending a twenty-year-old identical twin off in a rocket at very nearly the speed of light for two years (in his time), and have him return to find his brother a very old man living comfortably in Tucson, Arizona with the rest of the feeble old scientists who had shot him off into the ether seventy years earlier (in their time) in the first place.

The truth that rested in his theory of relativity also provided the unwanted proof of what an oily calm modern man had been sailing headlong into, somewhere en route ordaining the rest of the world should run adrift with him.

Despite the lingering influence of those such as Heidegger — with his modified Newtonian view of the present — it should have been apparent that in a world of space-time, the past, the present and the future all do exist quite simultaneously.

What modern man failed to realise Einstein was saying, was that time and space aren’t fixed or readily determinable; they are, in fact, infinitely variable. And while they do exist in a relative sense, there is nothing absolute in their nature. They are instead interwoven, making one quite inseparable from the other. So time exists for me in the space I occupy, and time exists for you in the space you occupy, but there are no grounds for the worn-out belief that time exists commonly and universally for the both of us.

That which modern man has known and thought of as time for so long is certainly no less real than the printing press or the motor car, but nor is it any less a product of his own invention.

Returning to Roger and Ruth’s question, “Is modernity our antiquity?” then, in terms of the world-view they perpetuate they could just as well be one in same. The failed linearity of time is inherent and intrinsic to both.

Friday, April 06, 2007

An Easter greetings.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Catedral Metropolitana, Mexico City, 1897. Albumen silver print, 23 x 18 cm, WF901020.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Catedral Metropolitana, Mexico City, 1897. Albumen silver print, 23 x 18 cm, WF901020.Is modernity our antiquity? What is bare life? Was tun? Worthy questions for this Easter season. More on these leitmotifs posed by the Documenta 12 team next week.

In the meantime, what a nutty world we live in when British soldiers leave their Iranian captors on BA business class, in new suits, with handsome show-bags in hand? Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in rabbit ears and a bushy tail. A pr coup or not, it was worth the chuckle heard round the world.

A warm Easter greetings to all.

Sunday, April 01, 2007

Was Tun? A video reply from Yusuf Islam.

In recent weeks I've been deliberating the Documenta 12 team's first leitmotif "Is modernity our antiquity?" As regular readers will know, I've taken the position that the Terror of History, as the late University of Chicago Professor Mircea Eliade coined it, leaves the question somewhat in tatters. While the team has also raised the more insightful question, "Which modernity and whose antiquity?", this line of questioning still marginalises those cultures wholly and voluntarily outside the Western paradigm.

On this rather beautiful spring morning here in Leipzig, I have decided to address the question today by simply shutting down my Powerbook and going for a walk. I leave you with something you'll likely enjoy much more than my usual pontification: a prayer for peace. Here Yusuf Islam (Cat Stevens) performs Heaven / Where True Love Goes at the Nobel Peace Prize Concert in Oslo, Norway, 11 December 2006.

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

Documenta 12 asks, "Is modernity our antiquity?" MZL wonders, or is it our Hotel California?

In deliberating the first of three leitmotifs posed by the Documenta team, "Is modernity our antiquity?", I've left little doubt in recent posts my feeling that modernity has come to its rightful end, just as antiquity did well before it, but the broader and more relevant question remains, have we actually escaped modernity or has it become our inescapable Hotel California? (At least not hearing the Eagles sing it again is escapable. I've chosen here a version by the Gypsy Kings while you ponder the question for 5 minutes, 47 seconds.)

Antiquity may be the basis of much that we in the West do and believe in, but it is not a universal paradigm, to the extent that modernity is. Every culture not only experiences a varying degree of impact from Western antiquity, but posseses its own distinct antiquity to reference as well. On the other hand, dead or alive, modernity remains as ubiquitous and unrelenting a force as ever across all the world's cultural boundaries (discussed in my previous posts), however late it might have arrived to some.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

What is bare life? Was ist das bloße Leben?

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Nietzsche 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.

Johann Dieter Wassmann, Nietzsche 306P, 1897. 370 x 280 x 100 mm.In recent posts I've been examining the first of three leitmotifs posed by the Documenta 12 team, "Is modernity our antiquity?" If I may, I'd like to skip ahead to the second question for a moment, "What is bare life?" as further means of addressing the first.

In 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown, often attributed to his contraction of syphilis, resulting in his admission to various clinics before he was moved to Naumburg, where his mother looked after him until her death in 1897. At this point his sister Elisabeth shifted him to Weimar, where she continued his care, as well as promoting his legacy and allowing the occasional audience with guests until his death in 1900.

It was in Weimar that Johann Dieter Wassmann briefly visited Nietzsche, but finding only a shell of a man he returned home to produce this work, depicting simply and eloquently the empty collar of the man, an organ stop with the name 'Nietzsche' printed on it, and an opium-stained bone apothecary spoon; a life stripped bare. These objects are placed against a dappled blue wall, reflecting Nietzsche's penchant for blue-lensed spectacles.

Johann's ability to take the contemporary moment of his visit with Nietzsche and so confidently convert it into the iconography of modernism speaks legions about the raw vitality of the modern movement at the dawn of the 20th century. In no time, however, modernity fell victim to the second law of thermodynamics, with entropy holding sway, but it was not until the close of the century that we realised the paradigm had simply collapsed en route.

Today it is essentially modernity stripped bare that we address as artists and curators, an ongoing post-mortem of abject failure. So in this sense is modernity our antiquity? The answer is not so clear.

Monday, March 12, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity? A video reply.

In tackling the question, "Is modernity our antiquity?" posed by the Documenta 12 team, I thought it might do, while we're still in the early stages of our discussion, to offer the podium to the Monty Python gang for a short reply with their immortal sketch Art Gallery.

Thursday, March 08, 2007

Is modernity our antiquity? A prologue.

In the first of a series, we invite writers to comment on the three leitmotifs posed by the Documenta 12 team. Here, Abigali von Bibra provides a short prologue to the question: Is modernity our antiquity? Abigail von Bibra teaches linguistics in Paris. She is writing a history of Prussian gender roles.

In the first of a series, we invite writers to comment on the three leitmotifs posed by the Documenta 12 team. Here, Abigali von Bibra provides a short prologue to the question: Is modernity our antiquity? Abigail von Bibra teaches linguistics in Paris. She is writing a history of Prussian gender roles.Every generation has its defining moments. The death of a leader. The collapse of commerce. The emergence of a nation from war. In due course, these events come to form a special kind of ground zero for the generations that follow. The chronicle of these and still lesser events falls together in what is at best a connect-the-dots manner, with one event crudely linked to the next. The picture that emerges is our skeletal image of history -- a working sketch held in general agreement upon which ‘definitive’ histories are then forged (yes, a double entendre). With these simple drawings in hand, the interpreters get down to business, over-painting their canvases in rich hues of red or yellow or white or black or whichever colour -- in whatever form and density -- the interpreter’s school of thought believes is relevant amid the cross-currents and undertows of the era. In this fashion, a portrait of history comes into being, with no two quite the same.

The Battle of Leipzig is one such defining moment, not just for Napoleon and Europe, but as well for three generations of Saxon cabinet-makers whose lives spanned the 19th century. The latter of the three -- Johann Dieter Wassmann – would come to pioneer early German modernism, but it is The Battle of Leipzig that most clearly informs his craft. These art works are boxed curiosities, falling somewhere between wunderkammern and Joseph Cornell, but what Johann’s boxes house are the anxieties of an era in which changes in science, medicine, industry and political philosophy have moved beyond the salons of noblemen and academics, engulfing the very real lives of the peasantry and guild classes.

Through this collection of boxes -- a collection which was once exhibited under the title ‘Bleeding Napoleon’ -- a portrait emerges in which we see a man not overly rapt with all that was taking place around him. Circumstance and good fortune made him witness to the worst and best the century had to offer, but the works themselves reflect a more focused concern. From the busy playfulness of his early pieces, to the spare elegance of his final efforts, these ‘worlds in a small room,’ as one critic has called them, are tinged with regret for what Johann perceived as the senseless separation of space (read here as Nature) from time, an apprehension that is no less endemic to our own age.

The Battle of Leipzig is an ominous moment on which to build a narrative, but it is a widely shared narrative, so much so that numerous writers and historians through the years have posited this catastrophic battle as the birth of modernity itself.

Book-ended by Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign the previous winter, and his defeat at Waterloo two years later, the battle is sometimes brushed past as a mere footnote on the road to Napoleon’s defeat. It was a bit more than that: this three-day engagement in 1813 was the greatest and bloodiest single battle of the 19th century. Never before in the history of mankind and never again until the First World War did half a million troops come face to face on the battlefield. The build-up began in the early weeks of October, the French and Allied armies assembling along a sixteen mile front east and southeast of the city. On the 16th of the month the first shots were fired; 72 hours later, Napoleon and his few remaining troops were fleeing for Paris. During this bat of an eye, 94,000 combatant casualties were incurred and 30,000 French troops were taken prisoner -- half on the battlefield, the remainder plucked from the hospitals of Leipzig. In addition, untold civilian casualties were inflicted by the vagaries of artillery used so close to an urban population.

If there had been any doubt previously, there was little doubt by 19 October 1813 that the modern era was fully upon us.

Wednesday, March 07, 2007

Q: Is modernity our antiquity? A: Like dah, Roger.

Pictured: recent restoration work at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Photo: Sophie Vogt.

Pictured: recent restoration work at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Photo: Sophie Vogt.In the first of their three leitmotifs, Documenta 12's co-directors Roger Buergel and Ruth Noack pose the question: Is modernity our antiquity? In a weighty TASCHEN mag just out titled Modernity? they ask magazine editors from around the world to pursue this question as it relates to their own cultural and historical circumstance.

To quote from the editorial to the first issue of the magazine: Which Modernity and whose Antiquity?, "The history of modernity can be told in many different ways. The authors featured in this issue therefore write about specific, local modernities, trace their dislocated or interrupted developments, explore counter- or parallel models of modernity in which undeveloped or unintended transitions and unexpected connections between spaces and practices come to light."

As an institution devoted to furthering our understanding of one of great pioneers of the early modernist movement -- Johann Dieter Wassmann -- we will be pursuing this question ourselves in coming weeks here on the MuseumZeitraum blog, while looking at the relevance of such questions in the context of our current post-colonial era.

Readers comments are willkomen!

Monday, March 05, 2007

Documenta 12... at your newstand now!

Last week I attended the launch at Vienna's Secession of Documenta 12's first magazine, Modernity?, not to be confused with Modern Maturity in case your news agent just looks at you clueless. If he doesn't already have it right up there next to Architectural Digest, you may need to explain to him that as the platform for this year's D12, artistic director Roger M. Buergel (pictured centre) and his partner Ruth Noack are using the medium of the magazine to prefigure three questions -- or leitmotifs as they describe them -- that the exhibition itself will address this summer in Kassel:

Last week I attended the launch at Vienna's Secession of Documenta 12's first magazine, Modernity?, not to be confused with Modern Maturity in case your news agent just looks at you clueless. If he doesn't already have it right up there next to Architectural Digest, you may need to explain to him that as the platform for this year's D12, artistic director Roger M. Buergel (pictured centre) and his partner Ruth Noack are using the medium of the magazine to prefigure three questions -- or leitmotifs as they describe them -- that the exhibition itself will address this summer in Kassel:Is modernity our antiquity?

(Ist die Moderne unsere Antike?)

What is bare life?

(Was ist das bloße Leben?)

What is to be done?

(Was tun?)

If he's still not impressed, you might add that ninety-one editors from around the world were asked to respond to these questions, with this handsome tome published by TASCHEN the result. The latter two questions will be explored in the next two issues, Life! and Education, which he should be ordering for display in April and May, respectively.

MuseumZeitraum Leipzig will also be weighing into the debate in the coming months, so do stayed tuned for that cherished, if a little out-of-kilter perspective you've all come to know and love.

Saturday, March 03, 2007

This week in Wolfsburg

"For me, painting means the continuation of dreaming by other means," Neo Rauch tells Jan Thorn-Prikker of the Goethe-Institut in an online interview just out. While some might think the New Leipzig School's 15 minutes are up -- or oughtta be -- Thorn-Prikker does a nice job of bringing us up-to-date on the occasion of Neo's show at the Wolfsburg Art Museum (current until 11 March). Image: Neo Rauch, Regal 2000, courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg.

"For me, painting means the continuation of dreaming by other means," Neo Rauch tells Jan Thorn-Prikker of the Goethe-Institut in an online interview just out. While some might think the New Leipzig School's 15 minutes are up -- or oughtta be -- Thorn-Prikker does a nice job of bringing us up-to-date on the occasion of Neo's show at the Wolfsburg Art Museum (current until 11 March). Image: Neo Rauch, Regal 2000, courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg.

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

The road to Ouagadougou

Earlier this week, we said a fond farewell to Australian film-maker and director of the Melbourne International Film Festival, Richard Moore, who's hot on the festival circuit this month. Last week: Berlin; this week: Burkina Faso. To explain, the Pan-African Film and Television Festival, Fespaco, a biennial event that's been running since 1969, is held in Ouagadougou, the Burkina Faso capital.

As regular readers will know, Richard is also producing The Foundation, a documentary on the life and work of Johann Dieter Wassmann. Finance is still pending and we're not sure he'll find it in west Africa, but stranger things have happened. Our Washington, D.C. benefactor, Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann, sent us an email Sunday night after watching the Academy Awards, advising Richard to head a little further west. To his surprise, an old classmate at Northwestern, David T. Friendly, was up for an Oscar for Best Picture as producer of Little Miss Sunshine.

As regular readers will know, Richard is also producing The Foundation, a documentary on the life and work of Johann Dieter Wassmann. Finance is still pending and we're not sure he'll find it in west Africa, but stranger things have happened. Our Washington, D.C. benefactor, Wassmann Foundation director Jeff Wassmann, sent us an email Sunday night after watching the Academy Awards, advising Richard to head a little further west. To his surprise, an old classmate at Northwestern, David T. Friendly, was up for an Oscar for Best Picture as producer of Little Miss Sunshine.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

Joseph Beuys on MTV. Who knew?

While I'd like to think the surprising popularity of our MuseumZeitraum Channel on YouTube was a result of our in-house content, our web-tracking would suggest our favourites page has something to do with it as well. Here you’ll find archival footage of Man Ray, Jean-Michel Basquiat, William Eggleston and Hans Richter, among others, as we continue to add rare oddities such as the immortal Art Gallery sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus and this most-amusing music video clip from Joseph Beuys, Sonne Statt Reagan.

Friday, February 23, 2007

Jörg Herold at The Armory Show

If you’re in New York this weekend and lucky enough to be heading to the Armory Show, make certain you stop by Leipzig’s Galerie EIGEN + ART, where you’ll find the enigmatic paintings of Jörg Herold. While Neo Rauch is most often identified with the New Leipzig School, insiders will know Jörg has long been Leipzig’s answer to Joseph Beuys (although, to be accurate, he now paints in Berlin and Mecklenburg).

His current show at EIGEN + ART, "The Caucasian: Looking at the findings of Herr Blumenbach," has left the city entranced since it opened a month ago. While I’d love to show you an example of his work, Galerie Direktor Herr Gerd Harry Lybke is a little jumpy about copyright, so I’ll just give you a link and let you see for yourself. Make certain you click through to his exhibition catalogue down the bottom of the page, a slow-loading pdf with a nice overview of his work through the years. Much of the text is in English, and well-worth a quick read.

His current show at EIGEN + ART, "The Caucasian: Looking at the findings of Herr Blumenbach," has left the city entranced since it opened a month ago. While I’d love to show you an example of his work, Galerie Direktor Herr Gerd Harry Lybke is a little jumpy about copyright, so I’ll just give you a link and let you see for yourself. Make certain you click through to his exhibition catalogue down the bottom of the page, a slow-loading pdf with a nice overview of his work through the years. Much of the text is in English, and well-worth a quick read.

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

iMuseum for an iNation

MuseumZeitraum Leipzig presents the 2-minute museum: iMuseum for an iNation. For more videos exploring the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann, please visit our newly-opened MuseumZeitraum channel on Youtube.

Monday, February 19, 2007

Thank you!

A special thanks to the editors of the American art magazine Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge. Their peer-reviewed on-line journal Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures has given us top billing, describing our YouTube channel as, "(A) fascinating collection of early German modernist film from the MuseumZeitraum Leipzig."

A special thanks to the editors of the American art magazine Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge. Their peer-reviewed on-line journal Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures has given us top billing, describing our YouTube channel as, "(A) fascinating collection of early German modernist film from the MuseumZeitraum Leipzig."

"Tuya's Marriage" takes home the Golden Bear

I'm now back in Leipzig after a lively, but exhausting 10 days in Berlin. The word came down before I left last night that director Wang Quan'an has won this year's Golden Bear at the 57th annual Berlinale. His film "Tuya's Marriage" follows the troubles of a young shepherdess in fast-changing rural China.

I'm now back in Leipzig after a lively, but exhausting 10 days in Berlin. The word came down before I left last night that director Wang Quan'an has won this year's Golden Bear at the 57th annual Berlinale. His film "Tuya's Marriage" follows the troubles of a young shepherdess in fast-changing rural China.The movie stars Yu Nan (pictured with Quan'an) as Tuya, a herdswoman on the steppe of Inner Mongolia trying to resist pressure to leave her pastures and move to the city as China's industry expands.

She and her handicapped husband, Bater, decide to get divorced after she falls ill, and Tuya seeks a respectable new husband who can look after Bater and her two children. An old classmate appears to fill that role, and he persuades Tuya and the children to move to town. (Yes, I just pinched that from the press release -- too tired to make up something original -- but it was a charming film.)

"A very beautiful dream has become reality for me here," director Wang told the press after receiving the Golden Bear statuette on Saturday. He said he believed the award "will bring good fortune to Chinese cinema."

Friday, February 16, 2007

And the winner is...

As the Berlinale draws to a close this weekend, all bets are off as to who might take home the coveted Golden Bear. The last films in Competition have proven to be several of the strongest, with plenty of surprises among them.

As the Berlinale draws to a close this weekend, all bets are off as to who might take home the coveted Golden Bear. The last films in Competition have proven to be several of the strongest, with plenty of surprises among them. Korean director Park Chan-wook's off-the-wall romantic comedy I'm a Cyborg, But that's OK (Sai bo gu ji man gwen chan a) quickly emerged mid-festival as a quirky possibility. The film tells the story of the love affair between two inmates in a psychiatric hospital, one of whom thinks she's a robot (or cyborg).

Another late starter is Irina Palm, starring Marianne Faithful, a tragic comedy from Belgian director Sam Garbarski, about a middle-class London grandmother, Maggie (of course), who is forced take a job as a 'hostess' in the city's sex industry to help pay her sick grandson's medical bills.

Popular with audiences has been American actor-turned-director Robert De Niro's (above - sorry, the best I could do) The Good Shepherd, which tells a John Le Carre-style story about the early days of the US Central Intelligence Agency. Equally popular has been Vienna-born director Stefan Ruzowitzky's The Counterfeiters (Die Faelscher), which recounts the true story of a plot hatched by the Nazis to ruin the Allies economies by forcing Jewish prisoners to fake US and British bank notes.

Among the last films to open has been Desert Dream (Hyazgar) by Chinese-Korean director Zhang Lu, which is set in the hostile wasteland on the border between China and Mongolia. Another film set in Mongolia that may be the dark horse is the wonderful Tuya's Marriage (Tu ya de hun shi) by Chinese director Wang Quan'an.

At the end of the bill is legendary Czech director Jiri Menzel's I served the King of England, about a young man's rise through Czech society.

Every jury has a mind of it's own, so I wouldn't even hazard a guess with so many willful contenders in the running.

Who's MoMA watching?

While you’re watching Doug Aitken’s latest work Sleepwalker projected onto the side of the Museum of Modern Art, ever wonder who MoMA's watching? Apparently, it’s MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. New Media curator Klaus Biesenbach (formerly of KW/Berlin) has just given our new work, Vorwärts!, a coveted listing on the Museum of Modern Art’s YouTube channel. Have a look at the trailer to Sleepwalker, then scroll down and click on my name, which will take you to our MuseumZeitraum channel. Many thanks, Klaus, and sorry we couldn’t catch up here at the Berlinale.

While you’re watching Doug Aitken’s latest work Sleepwalker projected onto the side of the Museum of Modern Art, ever wonder who MoMA's watching? Apparently, it’s MuseumZeitraum Leipzig. New Media curator Klaus Biesenbach (formerly of KW/Berlin) has just given our new work, Vorwärts!, a coveted listing on the Museum of Modern Art’s YouTube channel. Have a look at the trailer to Sleepwalker, then scroll down and click on my name, which will take you to our MuseumZeitraum channel. Many thanks, Klaus, and sorry we couldn’t catch up here at the Berlinale.

Thursday, February 15, 2007

To market, to market…

As if 373 films isn’t a few too many to take in over 10 days at the Berlinale, pity the poor punters a few block away at Martin Gropius Bau, where this year’s European Film Market is being held concurrently. With the rights to 702 films on the block, the euros are flowing fast as distributors and financiers scoop up next year’s hits and flops.

As if 373 films isn’t a few too many to take in over 10 days at the Berlinale, pity the poor punters a few block away at Martin Gropius Bau, where this year’s European Film Market is being held concurrently. With the rights to 702 films on the block, the euros are flowing fast as distributors and financiers scoop up next year’s hits and flops.I slipped into the 19th century museum, designed by and named for the uncle of Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius, with Melbourne International Film Festival director Richard Moore. Moore, as regular readers will know, is currently producing The Foundation, a film focusing on the art and life of Johann Dieter Wassmann and the efforts of MuseumZeitraum Leipzig to repatriate his works from Washington.

This is truly the business end of film; fat-cats lurk in every corner negotiating with affable film-makers hoping to pay off their debts and find a screen to show their dreams on. Better you than me, Richard.

For what it’s worth, one unlit-cigar-chomping English exec told us the big buzz is as follows: a culture clash romantic comedy by Julie Delpy, the latest project from Park Chan-wook, a new top secret documentary by Morgan Spurlock (Super Size Me) that The Weinstein Company scooped up and David Mackenzie's Competition entry Hallam Foe.

Controversy rocks Berlinale (so what’s new?)

Bille August’s film Goodbye Bafana, an early front-runner for the coveted Golden Bear (see below) has been rocked by controversy at this year's Berlinale, with accusations that James Gregory‘s autobiography on which the film was based were largely fabricated. Gregory’s story recounts a 20-year relationship between himself -- a former prison guard -- and his prisoner -- Nelson Mandela. The film has been warmly received by audiences here in Berlin.

Meanwhile in South Africa, Mandela's official biographer, Anthony Sampson, has accused Gregory of a gross distortion of the truth. According to Sampson, Gregory rarely spoke to Mandela in all those years and he’s claiming Gregory used information from a letter Mandela wrote to him to fabricate his friendship with the civil rights' leader.

With dark clouds rising, insiders say it’s doubtful the jury would risk their own reputation on August’s earnest effort.

Meanwhile in South Africa, Mandela's official biographer, Anthony Sampson, has accused Gregory of a gross distortion of the truth. According to Sampson, Gregory rarely spoke to Mandela in all those years and he’s claiming Gregory used information from a letter Mandela wrote to him to fabricate his friendship with the civil rights' leader.

With dark clouds rising, insiders say it’s doubtful the jury would risk their own reputation on August’s earnest effort.

Tuesday, February 13, 2007

Berlinale and the Golden Bear favourite

The jury (pictured above) is still out on who might win the coveted Golden Bear at this year's Berlinale, but the early audience favourite would have to be two-time Oscar-winner Bille August's latest film, Goodbye Bafana. The international co-production tells the true story of James Gregory (Joseph Fiennes), the white prison guard whose life was forever altered when he met the prisoner Nelson Mandela, whom he would become responsible for guarding for well over twenty years. Dennis Haysbert plays the ANC activist and later Nobel Peace Prize winner. This past Sunday marked 17 years since Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

The jury (pictured above) is still out on who might win the coveted Golden Bear at this year's Berlinale, but the early audience favourite would have to be two-time Oscar-winner Bille August's latest film, Goodbye Bafana. The international co-production tells the true story of James Gregory (Joseph Fiennes), the white prison guard whose life was forever altered when he met the prisoner Nelson Mandela, whom he would become responsible for guarding for well over twenty years. Dennis Haysbert plays the ANC activist and later Nobel Peace Prize winner. This past Sunday marked 17 years since Nelson Mandela was released from prison.For a lengthy and appropriately gushing review, have a look at critic Erik Davis's piece, which opens, "Every once in a blue moon you stumble across a perfect movie -- one that gets it all right -- and flows slow (sic) smoothly from start to finish, you almost wish it could go on and on ... and on. This year, in Berlin, Goodbye Bafana is that film." (Does it sound like he's bidding for a spot on the poster? No matter. The film is that good.)

Monday, February 12, 2007

Magnum in Motion

This year’s Berlinale has countless gems beyond the red carpet, from Generation, a section focusing on children’s film, to Culinary Cinema - Eat, Drink, See Movies. The star attraction for me, however has been Magnum in Motion, a selection of 33 films by and about the co-operative agency’s remarkable photojournalists. In attendance have been many of the greats, including René Burri (pictured), Raymond Depardon, Elliott Erwitt, Martine Franck, Jean Gaumy, Bruce Gilden, Philip Jones Griffiths, Thomas Hoepker, David Hurn, Susan Meiselas, Chris Steele-Perkins, Dennis Stock and Donovan Wylie.

This year’s Berlinale has countless gems beyond the red carpet, from Generation, a section focusing on children’s film, to Culinary Cinema - Eat, Drink, See Movies. The star attraction for me, however has been Magnum in Motion, a selection of 33 films by and about the co-operative agency’s remarkable photojournalists. In attendance have been many of the greats, including René Burri (pictured), Raymond Depardon, Elliott Erwitt, Martine Franck, Jean Gaumy, Bruce Gilden, Philip Jones Griffiths, Thomas Hoepker, David Hurn, Susan Meiselas, Chris Steele-Perkins, Dennis Stock and Donovan Wylie.And here’s the list of works on view over these two weeks. Read and weep:

Documentaries, short films and other formats:

A Peruvian Equation by Gilles Peress, USA, 1992

Beauty Knows No Pain by Elliott Erwitt, USA, 1971

Behind The Veil by Eve Arnold, UK, 1969

El Otro Lado/The Other Side by Alex Webb, USA, 1992

Getting Out by Eli Reed, USA, 1992

Jab Jab by Bruce Davidson, USA, 1992

La Boucane (The Smoking House) by Jean Gaumy, France, 1984

Le Retour (The Return) by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Lieutnant Richard Banks, USA, 1945

L’Espagne Vivra (Spain Will Live) by Henri Cartier-Bresson, France, 1938

Letting Go by Paul Fusco, USA, 1992

On The Rowanlea Trawler by Jean Gaumy, France, 1992

Pictures From A Revolution by Susan Meiselas, Alfred Guzetti and Richard Rogers, USA, 1991

Sous-Marin (Submarine) by Jean Gaumy, France, 2006

The Russian Prison by Gueorgui Pinkhassov, USA, 1992

The Train by Donovan Wylie, UK, 2001

Think Of England by Martin Parr, UK, 1999

Tod Im Maisfeld (Death In A Cornfield) by Thomas Hoepker, Germany, 1998

Two Faces Of China by René Burri, USA, 1968

Waiting For Madonna by Peter Marlow, USA, 1992

What Has Happened To The American Indians? by Martine Franck, France, 1970

Where Have You Been, Jimmy Dean? by Dennis Stock, France/USA, 1991

Sunday, February 11, 2007

Lagerfeld Confidential premiers at Berlinale

Last night I took in Rodolphe Marconi's Lagerfeld Confidential, which was a bit like sitting through 88 minutes of E! Like so many of the Berlinale events, however, the venue itself was worth the price of admission. The fabulous Kino International remains a show-piece of 'GDR modernism'; built in the early 1960s, it retains the great optimism and idealism of an era when East Berlin was the unofficial capitol of the Eastern Bloc. Strolling down Karl-Marx-Allee to the Kino today one can easily picture the throngs from across communist Europe coming to see what a bright future the collective state held for their own towns and villages.

Last night I took in Rodolphe Marconi's Lagerfeld Confidential, which was a bit like sitting through 88 minutes of E! Like so many of the Berlinale events, however, the venue itself was worth the price of admission. The fabulous Kino International remains a show-piece of 'GDR modernism'; built in the early 1960s, it retains the great optimism and idealism of an era when East Berlin was the unofficial capitol of the Eastern Bloc. Strolling down Karl-Marx-Allee to the Kino today one can easily picture the throngs from across communist Europe coming to see what a bright future the collective state held for their own towns and villages. Mindful of this past, it was a little hard to take seriously the story in front of me and the gravity with which it was told -- that of a Hamburg-born fashion designer growing up in a wealthy family in Lübeck, his dash to Paris at a young age to construct himself as a great French couturist, and his reluctance to ever look back long enough to come to terms with his own distinct 'Germanness'. As a portrait of a very private man this riches-to-ragtrade story is useful, but let's hope the advertorial documentary doesn't become the new black.

Friday, February 09, 2007

Berlinale - Tales from the front

Pictured: Johann Dieter Wassmann, Leipzig, 1894. Photograph by Sigismund Jacobi.

Pictured: Johann Dieter Wassmann, Leipzig, 1894. Photograph by Sigismund Jacobi. This morning I caught up with Melbourne International Film Festival director Richard Moore at KW's Café Bravo on Augustraße, Mitte. With 300 films to secure for his own festival, he's a busy man. If that wasn't enough, he continues to work as a documentary film-maker. One of his current projects is The Foundation (click through to view the trailer on YouTube), the tale of Johann Dieter Wassmann's remarkable life and work. While funding remains an issue (when isn't it), I was pleased to learn he's pushing ahead, with development support from Film Victoria in his native Australia. Many thanks to all those at Film Victoria and our many readers and supporters who continue to believe Johann Dieter Wassmann's contribution to early German modernism is a story the world should hear.

I'm heading in shortly to see Petr Nikolaev's film It Gonna Get Worse. Hope that's not an omen.

Thursday, February 08, 2007

La Vie En Rose

The city was blanketed in snow today as the 57th Berlin International Film Festival got underway. Opening the festival was Olivier Dahan's La Vie En Rose, the story of the famed French chanteuse Edith Piaf, starring Marion Cotillard (above, right). Multiple screenings were held during the day to a generally positive response, although at 140 minutes it appeared to be beyond the attention span of several American critics. The red carpet has now been stored away to dry out and we're off to a Turkish restaurant south of the city, appropriately it's on Wassmannstraße.

The city was blanketed in snow today as the 57th Berlin International Film Festival got underway. Opening the festival was Olivier Dahan's La Vie En Rose, the story of the famed French chanteuse Edith Piaf, starring Marion Cotillard (above, right). Multiple screenings were held during the day to a generally positive response, although at 140 minutes it appeared to be beyond the attention span of several American critics. The red carpet has now been stored away to dry out and we're off to a Turkish restaurant south of the city, appropriately it's on Wassmannstraße.

Landscape and Memory

As a native Berliner who doesn't always make it back for the Berlin Film Festival, I tend to forget there's often something bittersweet about seeing this city come alive -- as it has in recent days -- in the lead-up to the Berlinale, opening in a few hours time. Berlin is a city that demands of its visitors a memory of its past and a knowledge of the layers that lie beneath.

As a native Berliner who doesn't always make it back for the Berlin Film Festival, I tend to forget there's often something bittersweet about seeing this city come alive -- as it has in recent days -- in the lead-up to the Berlinale, opening in a few hours time. Berlin is a city that demands of its visitors a memory of its past and a knowledge of the layers that lie beneath. As the starlets exit their limousines on Marlene-Dietrich-Platz tonight to strut the red carpet, one wonders how many will know or care that the Wall once stood within sight; just beyond echoes still haunt the 'death strip' where so many of our fellow Berliners died attempting to escape to the West. And how many tonight in their designer gowns will consider that to the north of Potsdamer Platz just a few hundred meters lies the The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.

Once the films begin, however, the joy and pride of hosting this festival rapidly consumes our emotions. Arguably, no other artistic medium so successfully expresses this layering of history, as well as the urgency and essentialness of collective memory. With 373 films on the roster, festival director Dieter Kosslick awakens us with the world's memory for two weeks, recorded by many of the best practitioners from around the globe working today. For that we are proud and we can only say, willkommen.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

Berlinale Eve

Just a quick note from the new Berlin Haupbahnhoft, where I've just arrived on the morning train. If you're packing to join us at the Berlin Film Festival, don't be misled by this brief ray of sunshine, snow is in the forecast all week, which is better than the sleet and rain I left an hour ago in Leipzig. No, I haven't seen William Dafoe, J Lo or Clint Eastwood yet here on the platform, but stay tuned, I'll be reporting all week from the Berlinale, which opens tomorrow night with Marion Cotillard in the premiere of French-born Olivier Dahan's new film about the life of singer Edith Piaf, La Vie en Rose.

Just a quick note from the new Berlin Haupbahnhoft, where I've just arrived on the morning train. If you're packing to join us at the Berlin Film Festival, don't be misled by this brief ray of sunshine, snow is in the forecast all week, which is better than the sleet and rain I left an hour ago in Leipzig. No, I haven't seen William Dafoe, J Lo or Clint Eastwood yet here on the platform, but stay tuned, I'll be reporting all week from the Berlinale, which opens tomorrow night with Marion Cotillard in the premiere of French-born Olivier Dahan's new film about the life of singer Edith Piaf, La Vie en Rose.

Tuesday, February 06, 2007

Render to Caesar what is Caesar's

After a weekend in Paris catching up with friends, I’m struggling to sleep on the ICE back to Leipzig, so I thought I’d do a quick post. I had the privilege earlier this evening of attending a Museum International-sponsored symposium on “Memory and Universality” at UNESCO headquarters. The topic of discussion specifically concerned the universal mission of museums vs. the massive transfers of cultural property over the course of modernity. The ‘universal museums’ were represented by Henri Loyrette, President Director, Musée du Louvre, Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum and Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of the Hermitage Museum. Those standing up for source countries included Alain Godonou, Director, École du Patrimoine Africain, Benin and Juan Antonio Valdés, San Carlos University, Guatemala.

After a weekend in Paris catching up with friends, I’m struggling to sleep on the ICE back to Leipzig, so I thought I’d do a quick post. I had the privilege earlier this evening of attending a Museum International-sponsored symposium on “Memory and Universality” at UNESCO headquarters. The topic of discussion specifically concerned the universal mission of museums vs. the massive transfers of cultural property over the course of modernity. The ‘universal museums’ were represented by Henri Loyrette, President Director, Musée du Louvre, Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum and Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of the Hermitage Museum. Those standing up for source countries included Alain Godonou, Director, École du Patrimoine Africain, Benin and Juan Antonio Valdés, San Carlos University, Guatemala.What I find frightening is how good these major museum directors are getting at talking-the-talk. I don’t know, maybe they’ve all been taking lessons from Michael Brand at the Getty Museum and Ron Lauder at the Neue, but whatever it is, these guys could still sell ice to an Eskimo while convincing him to hand over his igloo so they can ‘protect his cultural heritage.’ While it’s clear the pillaging of the past is well-and-truly over (and it’s a very recent past at that), their current position of appearing fully ‘open and transparent’ in their negotiations with source cultures, while not budging an inch when it comes to handing back all but the most blatantly stolen pieces, is a talent in itself.

In our own battle to repatriate the works of Johann Dieter Wassmann from Washington, D.C., we encounter this same rhetoric on a weekly basis. Whatever the newly-discovered cultural imperatives of these major institutions, as far as trustees are concerned, possession remains nine-tenths of the law.

Thursday, February 01, 2007

Sie Kommen

A viewer on our YouTube MuseumZeitraum Channel has raised the question of how Johann Dieter Wassmann’s works came to leave Germany for Washington, D.C. in 1910. The long answer can be found in my essay Sie Kommen on our website, but I’ll try to keep it blog-length here. After the death of Johann’s widow Anna in 1900 from pneumonia, his boxed constructions, photographs, writings and personal archives were stored in 56 crates on the Weimar estate of their daughter Ilsabein and her husband Edward Liszt. Arch-conservative Liszt viewed the works as inflammatory, but out of respect to Ilsabein saw to their proper care. Concerned with inquiries as to their whereabouts from Henry van de Velde, Liszt revealed his cache to Ilsabein’s second cousin, Frederick Wassmann, visiting from Washington, D.C. in 1910, arranging with Frederick for their surreptitious shipment to Washington. In the United States, Frederick could do little to promote the contents of his windfall with the growing spectre of war inciting strong anti-German sentiment. The crates remained in storage until 1930, when they are moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania by Gladys and Karl Wassmann, Sr. (pictured left, Karl was Federick’s nephew). Karl, Sr. died in 1966. Gladys died in 1969. In Gladys’ will, a small amount of money was left to establish a foundation, “dedicated to overseeing the scholarship, conservation, publication, exhibition and promotion of the writings, personal archives and constructed works of Johann Dieter Wassmann.” MuseumZeitraum is currently negotiating with The Wassmann Foundation for the repatriation of the works to his native Leipzig.